The Rage in Harlem

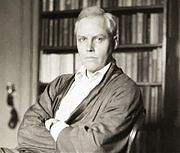

‘The Tastemaker,’ by Edward White

By BLAKE BAILEYFEB. 21, 2014

One of the milestones of modernism occurred in Paris on May 29, 1913, when “The Rite of Spring” debuted at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées and almost caused a riot. Startled by Stravinsky’s pounding rhythms and Nijinsky’s salacious choreography, the well-heeled philistines in the audience roared with disapproval while the connoisseurs, the happy few, tried shouting them down. One of the most memorable accounts of that first night was written by the American critic Carl Van Vechten, who allied himself decidedly with the latter camp, reporting that a kindred soul in the seat behind him was so carried away that he began beating a tattoo on the critic’s head with his fists. “My emotion was so great,” Van Vechten wrote, “that I did not feel the blows for some time.” Sharing his box was another pillar of the avant-garde, Gertrude Stein, who remembered certain details differently — as well she should, Van Vechten assured her. They had actually attended the less eventful second night of the ballet, but, as he suavely added, “one must only be accurate about such details in a work of fiction.”

A barely closeted gay man from a well-to-do family in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, Van Vechten was a gleeful champion of the provocative, and by God he was meant to be present at Stravinsky’s big night and the facts be damned. Isadora Duncan, Schoenberg, the blues — all were part of the cause, whatever struck the benighted as strange, ribald or downright grotesque. As Edward White writes in “The Tastemaker,” his ambitious and engaging portrait of a “polymath” and the world he helped shape, Van Vechten “collapsed the 19th-century distinctions between edifying art and facile entertainment, constantly probing the boundaries of what was considered good and bad taste.” Unsurprisingly, Van Vechten found his greatest happiness in popularizing the artists of the Harlem Renaissance: Paul Robeson, Josephine Baker, Langston Hughes and many others. Nor was this simply a matter of aesthetic preference. At his Manhattan apartment on West 55th Street, an almost utopian racial (and sexual) amity prevailed, with bons vivants of all colors drinking and dancing and coupling into the wee hours. Meanwhile, in the outside world, Van Vechten demonstrated for white society what he perceived to be the bracing emotionalism of African-American art, whooping and stomping his feet at, say, a Broadway revue featuring his friend Ethel Waters. So synonymous was he with “Negrophilia” that curious tourists who wandered into Harlem were said to be “van-vechtening” around.

Weary of his duties as a critic, Van Vechten reinvented himself as a novelist in the 1920s, arguably peaking in 1923 with his second novel, “The Blind Bow-Boy,” which White describes as “a masterpiece of camp, written decades before the term and concept came into existence.” Van Vechten’s ideal readership — those as naughty as he — could chuckle over characters like the Duke of Middlebottom, with his wistful motto, “A thing of beauty is a boy forever.” Innocents remained unperturbed.

Not so with respect to his fifth novel, a melodrama about the more lurid features of Harlem life that Van Vechten couldn’t resist titling “Nigger Heaven,” a colloquial (and obviously offensive) expression for the balcony seats in segregated theaters. Even the author’s Rotarian father objected in the strongest terms: “If you are trying to help the race as I am assured you are,” he wrote his son, “I think every word you write should be a respectful one towards the blacks.” Perhaps Van Vechten expected as much from the provinces, but surely his fellow sophisticates, black and white alike, would appreciate the title’s rightness, all the more because of the taboo it so blithely and ironically flouted.

Continue reading the main story

Or so he seemed to think, and for the most part he was disastrously mistaken. The black press was categorically scathing. (“Life to him is just one orgy after another,” W. E. B. Du Bois observed, “with hate, hurt, gin and sadism.”) Even among the author’s closest black friends there was more than a little ambivalence: While Langston Hughes and others defended Van Vechten’s right to depict the louche aspects of Harlem rather than write mere propaganda, Countee Cullen was one of many who remained implacably appalled by the book’s title alone — a typical failure on the part of blacks, as Van Vechten would have it, to recognize irony. White gives a nicely balanced account of this episode. Though Van Vechten’s views on racial difference could be condescending, he believed that such differences were nonetheless “axiomatic” and ultimately “a blessing.” They were “part of the rich diversity that made urban life in the United States such a thrilling experience,” as White puts it, while concluding all the same that Van Vechten should have known better than to produce a book with such an inflammatory title.

White shows a commanding grasp of the larger cultural ethos and Van Vechten’s place in it, and often his digressions about Hearst’s Chicago American (where Van Vechten cut his teeth as a journalist) or the arty salons in New York or the gay social mores of the era are more entertaining and astute than the biography of his subject per se. Indeed, White seems a little conflicted about where his proper focus should lie. Given that Van Vechten is anything but dull, I was puzzled by how relatively seldom White allows him to speak, and by the dim view he seems to take of Van Vechten personally. Again and again we are reminded of Van Vechten’s “contrary, self-centered nature.” Certainly this is true as far as it goes, but it hardly accounts for his popularity with such a diverse circle of friends.

Despite a vast archive of letters and diaries at Yale, White appears to rely heavily on a “meandering” (his word) interview that the almost 80-year-old Van Vechten gave to the Columbia Center for Oral History in 1960, at a time when he was reclusive, grouchy and perhaps a little frayed around the brain. “I was no particular use to him and he was less use to me,” Van Vechten said on this occasion with regard to Walter White of the N.A.A.C.P., whereupon the author rushes to underline, as ever, his subject’s callous narcissism: “From that casual remark one would never guess that Van Vechten was talking about an old friend who had actually named his son Carl in his honor.” Nor would one guess that Van Vechten was capable of such constancy as he showed Mark Lutz, a former lover with whom he exchanged notes almost daily for some three decades, and never mind his 50-year marriage to the actress Fania Marinoff, who must have found her husband awfully lovable in light of his attachments to Lutz and others.

To be sure, Van Vechten was fond of his own company, and why not? He bored easily, and by the age of 50 he’d met just about everyone he wanted to meet and had worked harder at his writing than he might have liked. His inheritance from a millionaire brother made it possible to devote himself to photography, which consumed him in a cheerfully desultory way for the last 30 years of his life. Practically every major cultural figure of the era was photographed by Van Vechten, whose favorite subject would always be himself. Profiled in The New Yorker shortly before his death in 1964, the all-but-forgotten polymath reflected on the many things he had accomplished, careful to emphasize that he still received some 25 letters a day from black admirers. “Though the world outside was changing as quickly now as when he first arrived in New York,” White concludes, “inside the sanctity of his own apartment Carl Van Vechten was still the only show in town.”

THE TASTEMAKER

Carl Van Vechten and the Birth of Modern America

By Edward White

Illustrated. 377 pp. Farrar, Straus & Giroux. $30.

Blake Bailey is the author of “Cheever: A Life.” His memoir, “The Splendid Things We Planned,” will be published next month.