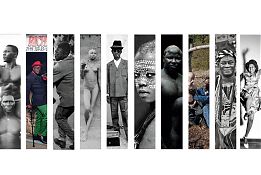

10 historical and contemporary photographers about Africa at Young Gallery

BRUSSELS.- Young Gallery Brussels presents an exhibition of 10 historical and contemporary photographers about Africa. These established and up and coming photographers from all over the world give their creative and original view of Africa.

Philippe Bordas was born in 1961. He is living and working in Paris. Director of the film “Grand combat” selected at the Venice Festival in 1996, he has exhibited his pictures all over the world. His photographic work joined his literary work, which began in 2008 with the publication of the highly acclaimed Madman. In 1993, he met the artist Frederick Bruly Bouabré writer he celebrates the poetic journey into the invention of writing (Fayard, 2010). From 1994 to 1999, he entered the closed world of the wrestlers of Senegal. The destinies of the boxers and wrestlers are the frame of the book text and photos bare knuckle Africa (Seuil, 2004. Nadar Prize), the first of a trilogy being editorial, exposed in 2004 at the Maison européenne de la photography. In early 2001, in Bamako, Philippe Bordas discovered the army of resurrected hunters from across West Africa, who had not recovered for nearly seven centuries. It will follow their travels for seven years.

Francesco Giusti lives and works in Rome, Italy. He recently won 1st Prize in the Viewbook Photostory competition for his documentary series, SAPE. A portrait story of the members of the SAPE from Pointe-Noire, Republic of the Congo.

In Congo-Brazzaville SAPE is an old passion that has never stopped, not even during war years. At the arrival of the French in Congo at the beginning of 9oo, the mith of elegance was born among young people working for the settlers.

In 1922, Andrè Grenard Matsoua, well-known for his resistance to the settlers, was the first Congolese to come back from Paris, well dressed like a true French “Monsieur”, greatly admired by all his fellow citizens.

Today’s members of the SAPE consider themselves as artists and are respected and admired by the whole community. “Sape is an art that is not referred to the means people have at their disposal. It’s a matter of harmony and matching colours”.

Making up his own clothes, choosing the right accessories, surely answers a clothing code as well as the pleasure of being unique and original. The members of the SAPE take a touch of glamour into their humble environment with their refined style and faultless clothes.

Austrian-born photographer Mario Marino has spent the last few months in the South Ethiopia’s Omo River Valley taking what he calls “photographic psychograms” of its inhabitants. Each gorgeously spare portrait represents a different micro-culture of the region, which Marino chose for its incredible density of distinct ethnic minorities. “Faces of Africa” is a race against time of sorts. Marino searches the smallest, furthest villages for people whose heritage is under assault by the potent forces of tourism, technological advancement, and social globalization.

His chosen method of preservation is to record a culture’s mark upon the body: white chalk used as face paint, intricate patterns shaved into hair, and throughout the portraits, ornaments made from the matchless leaves and shells of the South Ethiopian terrain. The sitters literally wear their homeland, supporting the claim of couturiers and choreographers everywhere that the body is simply one more medium for communication.

He has exhibited in Berlin, London and Munich.

Born in Lyon, France, Marc Riboud went to high school there and made his first picture in 1937 using his father’s Vest Pocket Kodak camera. He was active in the French Resistance from 1943 to 1945, then studied engineering at the Ecole Centrale from 1945 to 1948.

Until 1951 Riboud worked as an engineer in Lyon factories, but took a week-long picture-taking vacation, inspiring him to become a photographer.1 He moved to Paris where he met Henri Cartier-Bresson, Robert Capa, and David Seymour, the founders of Magnum Photos. By 1953 he was a member of the organization. His ability to capture fleeting moments in life through powerful compositions was already apparent, and this skill was to serve him well for decades to come.

Over the next several decades Riboud traveled around the world. In 1957 he was one of the first eurosopean photographers to go to China, and In 1968, 1972 and 1976, Riboud made several reportages on North Vietnam and later traveled all over the world, but mostly in Asia, Africa, the U.S. and Japan.

Riboud has been witness to the atrocities of war (photographing from both the Vietnam and the American sides of the Vietnam War), and the apparent degradation of a culture repressed from within (China during the years of Chairman Mao’s Cultural Revolution).

In contrast, he has captured the graces of daily life, set in sun-drenched facets of the globe (Fès, Angkor, Acapulco, Niger, Bénarès, Shaanxi), and the lyricism of child’s play in everyday Paris. In 1979 Riboud left the Magnum agency.

Riboud’s photographs have appeared in numerous magazines, including Life, Géo, National Geographic, Paris Match, and Stern. He twice won the Overseas Press Club Award, and has had major retrospective exhibitions at the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris and the International Center of Photography in New York.

He now lives in Paris

Here everyone aspires to become a living god. Nothing less. In the dark training rooms or on the beaches of the Dakar suburbs, where youngsters train themselves to Senegalese wrestling, everyone awaits feverishly the moment when they will have to wrestle under the burning sun, within the sand arena, in the middle of a stadium that gathers tens of thousands hungry spectators.

In order to give them the strength to face their sparring partner, the marabou will coat the wrestlers’ bodies with a potion; he will pour milk on their torsos, their shoulders, their heads, he will start singing the ritual words to cast evil spells away. The amulets they wear will protect them. Then, they will have to strike their opponents. Should one put his weight on his two legs and two arms, lie down on his back or fall out of the circle, then he will be defeated, or even worse, humiliated. Should one come out of the arena as a winner and the overexcited audience will acclaim him king. They might even become champions, wealthy and almost divine some day.

Denis Rouvre has photographed the strong bodies, the tense, perpetually defiant faces of the wrestling apprentices of suburbs of Dakar. They belong to one of the 77 stables of the country and they daily practice this unique sport activity as a subtle mix of traditional wrestling and bare hands boxing. The urbanization movement in the 70’s brought into the cities these traditional fights which were organized among the villages after harvest time. Wrestling became professional and included “boxing”. Punching was added to body contact. Fees that can be counted in millions of CFA Francs come now in addition to the sport and mystical challenge of the fight.

In the hidden training rooms of the streets of Dakar, they come every night with this dream in their minds and ready to take a lot of beating. They, who live on small jobs and tinker with their existence, are burning to strive against their sociological and human conditions. They want to become famous and superhuman. The names of their actual and past idols sound like those of gladiators: Tyson, Bomber, The Slaughterer, The Tiger of Fass, Pikine Hurricane. For this particular round that may change their lives, the wrestlers are ready to fight to death. The look in their eyes tells that they are lions already and that they will leap at the throat of those who will stand on the arena’s sand.

Malick Sidibé (born 1935 or 1936) is Malian photographer noted for his black-and-white studies of popular culture in the 1960s in Bamako. He was born in Soloba, Mali and completed his studies in design and jewelry in the École des Artisans Soudanais (now the Institut National des Arts) in Bamako.

In 1955, he undertook an apprenticeship at Gérard Guillat-Guignard’s Photo Service Boutique, also known as Gégé la pellicule. In 1958, he opened his own studio (Studio Malick) in Bamako and specialized in documentary photography, focusing particularly on the youth culture of the Malian capital. In the 1970s, he turned towards the making of studio portraits.

Malick Sidibé was able to increase his reputation through the first meetings on African photography in Mali in 1994. His work is now exhibited in Europe (for example, the Fondation Cartier in Paris), the United States and Japan. In 2003, Malick Sidibé received the Hasselblad Award for photography. He was awarded the Venice Biennale’s Golden Lion for lifetime achievement award in 2007. It was the first time it had been presented to a photographer. Malick Sidibé is represented by Fifty One Fine Art Photography, Antwerp. In 2006 Tigerlily Films made a documentary entitled “Dolce Vita Africana” about Malick, filming him at work in his studio in Bamako, having a reunion with many of his friends (and former photographic subjects) from his younger days and speaking to him about his work. In 2008, Malick Sidibé was awarded the ICP Infinity Award for Lifetime Achievement.

Today’s News

December 25, 2011