October 26, 2011

The Look of Love

By RANDY KENNEDY

The artist Nan Goldin has not lived full time in New York for several years, so the tiny apartment she keeps on West 14th Street feels more like a dorm room than a home, scattered with dog-eared books and mementos and a beaten-up scale model of the Matthew Marks Gallery, where a show of new work opens on Saturday, her first solo exhibition in the city since 2007.

On a recent visit Ms. Goldin took a while to emerge from her bedroom, whose door had a little picture of a snarling dog taped to it, with the handwritten warning: “Beware Mad Dog.” As if to underscore the point, a quite real-looking taxidermied coyote, which had once served as a prop on a photo shoot, crouched on one side of the living room facing out the balcony door, frozen in mid-howl. (“I can’t remember his name,” said Ms. Goldin’s studio manager, Clare Carter. “I think it’s Kevin or Scott or something.”)

Given this setup and the uncompromising autobiographical imagery for which Ms. Goldin has been known for much of her career — photographs of life lived at full tilt, of addiction and physical abuse, of friends and lovers ravaged by AIDS and other afflictions — it is not easy at first to reconcile her with the works arranged in tiny reproductions in the gallery model sitting on the floor.

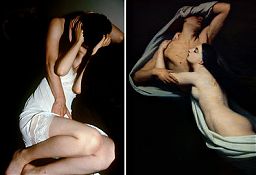

The pictures radiate a kind of Apollonian beauty, with flashes of details from paintings by Delacroix and Géricault peeping out among decades of Ms. Goldin’s plentiful nudes and pre- and post- and plain-old-coital scenes, whose punk bravado is softened and transformed by such High Romantic company.

The gathering of images is the culmination of an unusual partnership between Ms. Goldin, who has been living in Paris, and an art institution there that normally does business only with dead artists. For eight months last year the Louvre — at the suggestion of a guest curator, the French theater and film director Patrice Chéreau — allowed her to wander through its vast galleries at will with her camera on Tuesdays, when the museum is closed.

With a ladder and the help of a French photographer and friend, Fred Jagueneau, she enjoyed a rare kind of private communion with one of the finest collections of art in the world. And from the thousands of photographs she took of the paintings and sculptures, many of them obscure but some celebrated, she assembled an operatic 25-minute slide show, pairing Louvre images with many of her own dating back to the late 1970s.

Titled “Scopophilia” — a term that means simply “love of looking,” but that also refers to sometimes pathological sexual pleasure derived from gazing at bodily images — the film was first shown last winter at the Louvre along with some of the paintings Ms. Goldin loved. While the paintings had to remain in Paris, she decided to bring the photographs and film to New York, the city that has defined her career and life. (The show, at Matthew Marks on West 22nd Street in Manhattan, continues through Dec. 23.)

In a four-hour interview that began after Ms. Goldin finally emerged from her bedroom, lighted the first of a steady stream of American Spirit cigarettes and shooed everyone else from the apartment (“Everybody out!”), she said that her initial reaction to being offered free run of the Louvre was a kind of terror.

“I didn’t think I was qualified even to be in there,” she said. “I’m not an art historian, and I barely even went to school. I mean, I dropped out of high school. I did go to art school, but it was back in those days when that meant sitting outside in the car and getting high.”

But after many Tuesdays of uncertain wandering, she said that she reached a point when she stopped seeing the works in the museum as art-historical monoliths and began to see the figures on the plinths and within the frames almost as real people, ones she began to visit and photograph again and again. “It was one of the most sensuous experiences of my life,” she said. “And I’ve had a lot of sensual experiences in my life.”

Ms. Goldin, 58, moved to Paris in 2000 (“I couldn’t stay in the United States after Bush stole the election,” she said) and has become a darling of the French to rival Jerry Lewis and Mickey Rourke. The Pompidou Center mounted a retrospective in 2001, and in 2006 she was named a commander of the Order of Arts and Letters by the French government. But she said that being granted a private audience with the Louvre — “We ran around in there barefoot; there was absolutely nobody around” — brought a feeling of French acceptance unlike any she’d had before.

And the Louvre also quickly taught her, she said, that many of her artistic obsessions are ones that have been to central Western art history, and to myth and religious iconography — sex, violence, rapture, despair and the slippery nature of gender. She gravitated toward representations of the mythological tales popularized by Ovid, like the second-century Roman marble “The Sleeping Hermaphrodite,” whose male genitals come as a surprise to viewers approaching the curvaceous female form from the back. (The black-and-white work for which Ms. Goldin first became known involved transvestites and transsexual friends in Boston, where she was raised.)

More than half of the photographs by Ms. Goldin that she paired with Louvre imagery have never been exhibited before, and many were unearthed from her New York archives in a painstaking search by one of her assistants. But other pictures were resurrected by Ms. Goldin herself. An obsessive series of photographs she took of a former lover named Siobhan were included after Ms. Goldin re-established contact and the woman, now married and a mother, agreed to allow many never-before-seen images to be shown, “which is great,” Ms. Goldin said, “because it had been pretty painful for a lot of years not to show them.” Those photographs and many of the others she chose ended up creating a collective portrait more joyous than the kinds Ms. Goldin is known for. “It really became a work about love,” she said, one propelled by the love she felt inside the museum, “all of the pleasure circuits deeply fulfilled by looking.”

The only pain to come out of her time in the Louvre, she said, is felt when she returns to the museum now on days when it is open, “and I’m like: ‘Why are all these people looking at my paintings?’ It’s terrible for me.”

As the interview wound down, and a late afternoon rainstorm began to blow in, Ms. Goldin walked over to scoot the taxidermied coyote back a few inches from the open balcony door. “Isn’t he great?” she asked. “His name is Larry. I love him, but somehow he’s lost his tongue. We need to get Larry a new tongue.”