Ibrahim el-Salahi: Out of Africa

As a student in London in the 1950s, Sudanese-born Ibrahim el-Salahi was influenced by Western art. But it is the images from his homeland that most fascinate, says Adrian Hamilton

16 July 2013

Tate Modern is going African with parallel shows from two entirely different artists from across the continent. Ibrahim el-Salahi, born in 1930 and now retired to Oxford, is a veteran of the postwar renaissance in African art and its troubled politics. A minister one moment, imprisoned the next, his painting is a deeply personal search for forms that express his innermost yearnings and the anguish of his prison experience. Meschac Gaba, born in 1961, comes from Benin in West Africa, and is an installation and multidisciplinary artist intent on expressing what Africa means today.

There’s not much doubt as to who is the more significant. El-Salahi’s is the journey that painters have made through the ages and it is fascinating, and at times moving, to follow him on his. Born in Omdurman, where his father taught at a Quranic school, he studied art first in Khartoum, then at the Slade in London with time spent in Italy, before returning to teach in Khartoum. So far, so conventional and, indeed, the early works on display here show a talented graphic artist trying out the modern art learnt from the Western masters. Cubism, Picasso, Surrealism, a touch of Miró are all here. The Tate describes him as “a Visionary Modernist” and that is how he first projected himself on to the broader African art scene, both as a founding member of the Khartoum School, which took the calligraphy of Arabic scripts and broke them up into fragmentary shapes, and as an associate of the Mbari Club in Ibadan, Nigeria, which sought to make a wider-ranging African art.

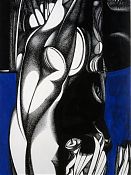

What makes him such an interesting artist, however, is less his experiments with form, striking although some of them are, than the sense of tension in his work between an intellect that seeks purity of expression and an imagination which wants to free itself from constraint. One is tempted to say that there is something very Islamic in this combination of the rigours of outward form and the intensity of inner yearning. Throughout his career, El-Salahi has incorporated into his pictures the crescent and moon of Muslim iconography along with the bird that is so often the symbol of hope and freedom in its tales.

But then there is also something very African in the earth colours and mask-like faces he chooses in works such as the Tate’s monumental Reborn Sounds of Childhood Dreams 1 of 1962-3, They Always Appear from 1966-8 and the touching The Last Sound of 1964, painted after his father’s death in which the spirit of the dead explodes with the dots and curves of Kufic Arabic writing.

El-Salahi’s own description of the way he manages his compositions is that he starts with a shape or image at the centre of the canvas and then works outwards, relying on spontaneous whim and urgings to fill out the picture. That helps to explain the vertical emphasis at the middle and the horizontal and carved shapes towards the sides. But they are still held by an overarching control which never allows the totally free association which the Surrealists sought. Like the Sufi singer, the ecstasy comes with the repetition and the chanting.

Control and imagination were both at a premium when the artist was suddenly imprisoned without charge in Sudan in 1975. He’d returned to Sudan with a growing international reputation from London, where he’d been assistant cultural attaché at the Sudanese Embassy, to become director of culture and then the under-secretary in the ministry. His dramatic incarceration was unexpected and humiliating. One moment a figure of rank, he became just another political prisoner in the notorious Cooper Jail in Khartoum North.

Anyone going to this exhibition should spend the 20 minutes or so looking on-screen at the successive pages of his prison notebooks along with his recorded explanation of the images and accompanying text.

The sketches and the poems, scribbled on paper scraps hidden in the dirt from the guards, tell of brute power, iron gates and blank skies, but also of the onion planted by the water gourds, the animal fables of his childhood and the presence of the little bird signifying liberty and conscience. Released as suddenly and wordlessly as he was arrested, El-Salahi eventually got out of the country to Doha and then to Britain. His pictures since leaving prison show an explosion of colour that freedom has brought but also a return to the black-and-white, thickly outlined, surrealistic figures of his earlier works, building on the graphic concentration he was forced into during prison.

A brilliant series of drawings on square sheets entitled Visual Diary of Time-Waste Palace show the artist trying to figure out his life in abstract diagrams, Picasso-like figures and cartoon-like doodling. The end result of this self-examination was, in 1997, an emphatic decision to give up all diversions and to concentrate on his art. A wry self-portrait, Head of the Undersecretary from 2000, has him turbaned in the greens of Islam, double-eyed with the bird whispering (or is it pecking?) into his ear.

Two themes have dominated his work since. One is versions of trees based on the haraz tree of the Nile, which conserves its moisture in the rainy season by letting its leaves brown and then burst into bloom when it is dry. More recently, he has done a series of paintings of flamenco dancers based on a visit to Granada in which he tries through thick outline to capture the stamping and furious energy of the gipsy dancers.

There’s too many of both trees and dancers to keep the Tate’s retrospective on an even keel, certainly with the dancers when he seems at times to be repeating himself for failure to quite express quite what it is that he wants. But one is never in any doubt that this is a creative mind in its eighties still trying to resolve itself in paint and to find the universality he reaches for. A fine artist, whatever his nationality.

After this it is a bit of a letdown to wander into Meschac Gaba’s 12-room Museum of Contemporary African Art on the same floor. There’s nothing wrong with it. There’s an architecture room in which you, or your child, can play with giant bricks, an art and religion room in which the popular symbols of every faith are mixed up on shelves, a museum shop, a music room with worn gramophone records and so forth, all heavy with the artefacts of African life and laced with the banknotes and security dots which are Gaba’s trademark indicators of the commercialisation dominating all of modern life. “Questioning the nature of the museum and the perceptions of African art” is how the curators like to summarise it.

But it all has a dated feel to it, starting life in 1997 in Amsterdam and expanding as it has toured since. It may wish to subvert the notion of museums but it seems very much a product of them. The Tate should have kept to El-Salahi. He’s worth it.

Ibrahim el-Salahi: a Visionary Modernist and Meschac Gaba: Museum of Contemporary African Art, Tate Modern, London SE1 (020 7887 8888) to 22 September