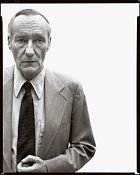

“Naked Lunch” brought to social notice themes of drug use, homosexuality, hyperbolic violence, and anti-authoritarian paranoia. Photograph by Richard Avedon.

“I can feel the heat closing in, feel them out there making their moves.” So starts “Naked Lunch,” the touchstone novel by William S. Burroughs. That hardboiled riff, spoken by a junkie on the run, introduces a mélange of “episodes, misfortunes, and adventures,” which, the author said, have “no real plot, no beginning, no end.” It is worth recalling on the occasion of “Call Me Burroughs” (Twelve), a biography by Barry Miles, an English author of books on popular culture, including several on the Beats. “I can feel the heat” sounded a new, jolting note in American letters, like Allen Ginsberg’s “I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness,” or, for that matter, like T. S. Eliot’s “April is the cruellest month.” (Ginsberg was a close friend; Eliot hailed from Burroughs’s home town of St. Louis and his poetry influenced Burroughs’s style.) In Burroughs’s case, that note was the voice of an outlaw revelling in wickedness. It bragged of occult power: “I can feel,” rather than “I feel.” He always wrote in tones of spooky authority—a comic effect, given that most of his characters are, in addition to being gaudily depraved, more or less conspicuously insane.

“Naked Lunch” is less a novel than a grab bag of friskily obscene comedy routines—least forgettably, an operating-room Grand Guignol conducted by an insouciant quack, Dr. Benway. “Well, it’s all in a day’s work,” Benway says, with a sigh, after a patient fails to survive heart massage with a toilet plunger. Some early reviewers spluttered in horror. Charles Poore, in the Times, calmed down just enough to be forthright in his closing line: “I advise avoiding the book.” “Naked Lunch” was five years in the writing and editing, mostly in Tangier, and aided by friends, including Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac. It first appeared in 1959, in Paris, as “The Naked Lunch” (with the definite article), in an Olympia Press paperback edition, in company with “Lolita,” “The Ginger Man,” and “Sexus.” Its plain green-and-black cover, like the covers of those books, bore the alluring caveat “Not to be sold in U.S.A. or U.K.” (A first edition can be yours, from one online bookseller, for twenty thousand dollars.) The same year, Big Table, a Chicago literary magazine, printed an excerpt, and was barred from the mails by the U.S. Postal Service. Fears of suppression delayed a stateside publication of the book until 1962, when Grove Press brought out an expanded and revised edition. It sold so well that Grove didn’t issue a paperback until 1966.

As late as 1965, however, a Boston court confirmed a local ban, despite testimony from Norman Mailer arguing the book’s literary merit. (Another supporter was Mary McCarthy, who, in the New York Review of Books, praised Burroughs’s “crankish courage” and compared “Naked Lunch” to “a worm that you can chop up into sections each of which wriggles off as an independent worm. Or a nine-lived cat. Or a cancer.”) A year later, the Massachusetts Supreme Court reversed the ban, on the ground of “redeeming social value,” a wobbly legal standard in censorship cases then and after. Thus anointed, Burroughs’s ragged masterpiece brought to social notice themes of drug use, homosexuality, hyperbolic violence, and anti-authoritarian paranoia. Those temerities and his disarmingly starchy public mien—he was ever the gent, dressed in suits, with patrician manners and a sepulchral, Missouri-bred and foreign-seasoned voice—assured him a celebrity status that is apt to flare anew whenever another cohort of properly disaffected young readers discovers him. The centenary of Burroughs’s birth, on February 5th, promises much organized attention; an excellent documentary by Howard Brookner, “Burroughs: The Movie” (1983), is about to be re-released.

Contrary to Kerouac’s mythmaking portrayal of him—as Old Bull Lee, in “On the Road”—Burroughs was not a wealthy heir, although his parents paid him an allowance until he was fifty. His namesake grandfather, William Seward Burroughs, perfected the adding machine and left his four children blocks of stock in what later became the Burroughs Corporation. His son Mortimer—the father of William and another, older son—sold his remaining share, shortly before the 1929 crash, for two hundred and seventy-six thousand dollars. Mortimer’s wife, born Laura Lee, never ceased to dote on William; Mortimer deferred to her.

Burroughs started writing at the age of eight, imitating adventure and crime stories. He attended a John Dewey-influenced progressive elementary school in St. Louis and played on the banks of the nearby, sewage-polluted River des Peres. Miles quotes him recalling, in a nice example of his gloatingly dire adjectival style, “During the summer months the smell of shit and coal gas permeated the city, bubbling up from the river’s murky depths to cover the oily iridescent surface with miasmal mists.” When Burroughs was fourteen, some chemicals he was tinkering with exploded, severely injuring his hand; treatment for the pain alerted him to the charms of morphine. He then spent two unhappy years at the exclusive Los Alamos Ranch School for boys, in New Mexico, memories of which informed his late novel “The Wild Boys” and other fantasies of all-male societies.

Burroughs was a brilliant student, graduating from Harvard with honors, in English, in 1936. He sojourned often in Europe; in Vienna, he briefly studied medicine and frequented the gay demimonde. He had become aware at puberty of an attraction to boys, and had been so embarrassed by a diary he kept of a futile passion for a fellow-student that he destroyed it and stopped writing anything not school-required for several years. Later, in psychoanalysis, he traced his sexual anxiety to a repressed memory: when he was four years old, his nanny forced him to perform oral sex on her boyfriend. The tumultuous experience of having his first serious boyfriend—in New York, in 1940—triggered what he laconically called a “Van Gogh kick”: he cut off the end joint of his left pinkie.

After a short hitch in the Army, in 1942, Burroughs received a psychiatric discharge. He then worked briefly as a private detective, in Chicago, where, however, he enjoyed his longest period of regular employment—nine months—as a pest exterminator. His delectable memoir of the job, “Exterminator!,” the title story of a collection published in 1973, employs a tone, typical of him, that begs to be called bleak nostalgia: “From a great distance I see a cool remote naborhood blue windy day in April sun cold on your exterminator there climbing the grey wooden outside stairs.”

The creation story of the Beats is by now literary boilerplate. Burroughs moved to New York in 1943, along with David Kammerer, a childhood friend who had travelled with him in Europe, and Lucien Carr, an angelically handsome Columbia University student whom Kammerer was stalking. Ginsberg, a fellow-student, was enthralled by Carr, and later dedicated “Howl” to him. Kerouac, who had dropped out of Columbia and served in the Navy, returned to the neighborhood in 1944. With Carr as the catalyst, and Burroughs, whom Kerouac goaded to resume writing, a charismatic presence, the Beat fellowship was complete.

Carr ended Kammerer’s pursuit of him late on the night of August 13, 1944, by stabbing him and dumping his body in the Hudson River. (The new movie “Kill Your Darlings” tells the tale in only somewhat embellished fashion.) Burroughs then replaced Carr as the group’s mentor. According to Miles, Kerouac and Ginsberg didn’t yet know that Burroughs was gay, and played matchmaker by introducing him to Joan Vollmer, an erudite, twice-married free spirit with a baby daughter, Julie, of uncertain paternity. Burroughs and Vollmer became inseparable and, they believed, telepathic soul mates, but he continued to have sexual encounters with men. In 1946, he started on heroin. (An uncle, Horace Burroughs, whom he idealized but never met, was a morphine addict who committed suicide in 1915, when the drug was legally restricted.) Vollmer favored Benzedrine.

Postwar New York updated Burroughs’s trove of criminal argot. He saw a lot of Herbert Huncke, a junkie and a jack-of-all-scams—whom Ginsberg called “the basic originator of the ethos of Beat and the conceptions of Beat and Square”—and other habitués of Times Square, whose doppelgängers roam the fiction that he had not yet begun to write. In 1946, Vollmer became pregnant. Burroughs, who could be startlingly moralistic, abhorred abortion; and so a son, Billy, joined the family. Envisioning himself as a gentleman farmer, Burroughs had acquired a spread in East Texas, where he cultivated marijuana, though not very well. He drove a harvest to New York with Kerouac’s “On the Road” icon, Neal Cassady—whom he disdained as, in Miles’s words, “a cheap con man”—but it was too green to turn a profit. After a drug bust in New Orleans, Burroughs jumped bail and settled in Mexico City. For three years, he took drugs, drank, picked up boys, hosted friends, and cut a sorry figure as a father. (With Vollmer also drinking heavily, the children’s lot was grim.) A Mexican scholar of the Beats, Jorge García-Robles, details the louche milieu in another new book, “The Stray Bullet: William S. Burroughs in Mexico” (Minnesota). He writes that Burroughs found the country “grotesque, sordid, and malodorous, but he liked it.”

During those years, Burroughs also wrote his first book, “Junky.” A pulp paperback published in 1953, under the pen name William Lee, it recounts his adventures through underworlds from New York to Mexico City. It features terse, crackling reportage, with echoes of Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler. The narrator’s first meeting with “Herman” (a pseudonym for Huncke) isn’t auspicious: “Waves of hostility and suspicion flowed out from his large brown eyes like some sort of television broadcast.” “Junky” attracted no critical notice. Burroughs wrote two other books in the early fifties that weren’t published until after “Naked Lunch.” “Queer”—centering, in Mexico City, on one of his arduous opiate withdrawals and a frustrating romance with a young man—saw print only in 1985. The most emotional work in a generally icy œuvre, it was written around the time, in 1951, of the most notorious event in Burroughs’s life: his fatal shooting of Vollmer, in a drunken game of “William Tell.”

García-Robles and Miles agree in their accounts of Vollmer’s death. At a friend’s apartment, she balanced a glass on her head, at Burroughs’s behest. He had contracted a lifelong mania for guns from duck-hunting excursions with his father, and was never unarmed if he could help it. He fired a pistol from about nine feet away. The bullet struck Vollmer in the forehead, at the hairline. She was twenty-eight. He was devastated, but readily parroted a story supplied by his lawyer, a flamboyant character named Bernabé Jurado: the gun went off accidentally. Released on bail, Burroughs might have faced trial had not Jurado, in a fit of road rage, shot a socially prominent young man and, when his victim died of septicemia, fled the country. Burroughs did the same, and a Mexican court convicted him in absentia of manslaughter, sentencing him to two years. In the introduction to “Queer,” Burroughs disparages his earlier work and adds, “I am forced to the appalling conclusion that I would never have become a writer but for Joan’s death,” because it initiated a spiritual “lifelong struggle, in which I have had no choice except to write my way out.” García-Robles avidly endorses this indeed appalling consolation, casting Vollmer as a sainted martyr to literature.

Miles relates that Burroughs had told Carr, after he killed Kammerer, “You shouldn’t blame yourself at all, because he asked for it, he demanded it.” Some of Burroughs’s friends, including Ginsberg, opted for an analogous understanding of Vollmer’s death as an indirect suicide, which she had willed to happen. Burroughs’s craving for exculpation eventually settled on the certainty that an “Ugly Spirit” had deflected his aim. As a child, Burroughs had been infused with superstitions by his mother and by the family’s Irish maid, and all his life he believed fervently in almost anything except conventional religion: telepathy, demons, alien abductions, and all manner of magic, including crystal-ball prophecy and efficacious curses. For several years in the nineteen-sixties, he enthusiastically espoused Scientology, in which he attained the lofty rank of “Clear,” before being excommunicated for questioning the organization’s Draconian discipline. And he furnished any place he lived in for long with an “orgone accumulator”—the metal-lined wooden booth invented by the rogue psychoanalyst Wilhelm Reich for capturing and imparting cosmic energy. Miles begins “Call Me Burroughs” with a scene of a sweat-lodge ceremony conducted by a Navajo shaman to finally expel the Ugly Spirit, in Kansas, in 1992. The heat and smoke caused Burroughs to ask to truncate the proceedings.

Vollmer’s parents took Julie into their home, in Albany, and she dropped out of her stepfather’s life. Burroughs sent Billy to be raised by Laura and Mortimer, in St. Louis, and joined them, in 1952, after they moved to Palm Beach, Florida. But he didn’t stay long; he set out to work on his third book, “The Yage Letters,” a quest through the jungles of Colombia for a fabled hallucinogen that, he had written in the last sentence of “Junky,” “may be the final fix.” He found and duly lauded the drug, but the journey seems its own reward, making for fine low-down travel writing. He needs a motorboat to take him upriver:

Sure you think it’s romantic at first but wait til you sit there five days onna sore ass sleeping in Indian shacks and eating hoka and some hunka nameless meat like the smoked pancreas of a two-toed sloth and all night you hear them fiddle-fucking with the motor—they got it bolted to the porch—“buuuuurt spluuuu . . . ut . . . spluuuu . . . ut,” and you can’t sleep hearing the motor start and die all night and then it starts to rain. Tomorrow the river will be higher.

The book wasn’t published until 1963. In the meantime, two volumes of a trilogy, “The Soft Machine” and “The Ticket That Exploded,” came out, soon followed by the third, “Nova Express.” These were written largely in London and Paris, between trips to Tangier, where Burroughs had lived for several years, starting in 1954. They advanced his claim (with some precedents in Dadaism and Surrealism) to literary innovation: the “cut-up” technique of assembling texts from scissored fragments of his own and others’ prose. The trilogy is a sort of fractured science fiction, telling of underground struggles against forces of “Control”—the shape-shifting, all-purpose bête noire of Burroughs’s world view. It is easier to read than, say, “Finnegans Wake,” but hard going between such bursts of dazzle as the “resistance message”:

A second trilogy—“The Cities of the Red Night,” “The Place of Dead Roads,” and “The Western Lands”—published between 1981 and 1987, reverts to fairly normal narration, filled with scenes of sexual and military atrocity in a succession of mythic cities. Its heroes include Hassan-i Sabbah, the historical leader of a sometimes homicidal sect in eleventh- and twelfth-century Persia. “Nothing is true, everything is permitted,” Sabbah is supposed to have said (and was so quoted by Nietzsche). The prose is nimble and often ravishing, but marred by the author’s monotonous obsessions and gross tics—notably, a descent into ferocious misogyny, casting women as “the Sex Enemy.”

The biography, after its eventful start, becomes rather like an odyssey by subway in the confines of Burroughs’s self-absorption, with connecting stops in New York, where he lived, in the late nineteen-seventies, on the Bowery, in the locker room of a former Y.M.C.A., and, returning to the Midwest, in the congenial university town of Lawrence, Kansas, where he spent his last sixteen years, and where he died, of a heart attack, in 1997, at the age of eighty-three. Miles’s always efficient, often elegant prose eases the ride, but a reader’s attention may grow wan for want of sun. Most of the characters run to type: dissolute quasi-aristocratic friends, interchangeable boys, sycophants in steadily increasing numbers. Names parade, from Paul Bowles and Samuel Beckett (who, meeting Burroughs at a party in Paris, denounced the cut-up method as “plumbing”), through Mick Jagger and Andy Warhol, to Laurie Anderson and Kurt Cobain. Most prominent is Brion Gysin, a mediocre artist of calligraphic abstractions. Burroughs met him in Tangier, in 1955, and bonded with him in Paris at a dump in the Latin Quarter, known as the Beat Hotel, whose motherly owner adored literary wanderers.

Gysin and Burroughs deemed each other clairvoyant geniuses. They collaborated on cut-ups, extending the technique to audiotape, and foresaw commercial gold for Gysin’s “Dreamachine,” a gizmo that emitted flickering light to mildly hypnotic effect. It flopped. Burroughs took to making art himself, especially after Gysin’s death, in 1986: he created hundreds of pictures, on wood, by shooting at containers of paint. These have been widely exhibited and sold. They are terrible. Burroughs had no visual equivalent of the second-nature formality that buoys even his most chaotic writing.

Ginsberg comes off radiantly well in Miles’s telling, as a loyally forgiving friend. He tolerated Burroughs’s amatory passion for him, which developed in the fifties, as long as it lasted. Much of Burroughs’s best writing originated in letters to the poet, who took a guiding editorial hand in it. It was Ginsberg who hatched the title “Naked Lunch,” by a lucky mistake, having misread the phrase “naked lust” in a Burroughs manuscript. (I think of Ezra Pound’s editorial overhaul of “He Do the Police in Different Voices”—Eliot’s first title for “The Waste Land.”) Ginsberg effectively sacrificed his own literary development, which sagged after “Kaddish” (1961), to publicizing his friends and, of course, himself. Burroughs disparaged his puppylike attendance in Bob Dylan’s entourage. (Burroughs’s aloofness, like his obsession with mind control, reflected memories of a reviled uncle, Ivy Ledbetter Lee, a pioneering public-relations expert whose clients included John D. Rockefeller and the Nazi Party.) But Burroughs liked his own growing fame. He gave readings to full houses. Appearances on “Saturday Night Live,” in 1981, and in Gus Van Sant’s “Drugstore Cowboy,” in 1989, spread the popularity of his gentleman-junkie cool.

The biography’s most painful passages involve Billy, who both idolized and, for excellent reasons, resented Burroughs. What might you be like, had your father killed your mother and then abandoned you? In 1963, when Billy was sixteen, Burroughs, bowing to his parents’ insistence, briefly took charge of the troubled lad in Tangier. The main event of the visit was Billy’s introduction to drugs, condoned by Burroughs. In and out of hospitals and rehabs, Billy wrote three novels, of which the first, “Speed” (1970), detailing the ordeal of amphetamine addiction, showed literary promise. In 1976, father and son reunited at the Naropa Institute, in Boulder, where Ginsberg and other poets had initiated a program in experimental writing, and where Burroughs was teaching, with crotchety flair. Billy, who had received a liver transplant for cirrhosis, engaged in spectacular self-destruction. Miles writes, “Billy wanted Bill to witness the mess he was in; he was paying him back.” Billy died in 1981, at the age of thirty-three. Burroughs seemed to regret only that he had not sufficiently explained the Ugly Spirit to him. He responded to his son’s death by varying his current methadone habit with a return to heroin.

“Virtually all of Burroughs’s writing was done when he was high on something,” Miles writes. The drugs help account for the hollowness of his voices, which jabber, joke, and rant like ghosts in a cave. He had no voice of his own, but a fantastic ear and verbal recall. His prose is a palimpsest of echoes, ranging from Eliot’s “Preludes” and “Rhapsody on a Windy Night” (lines like “Midnight shakes the memory / As a madman shakes a dead geranium” are Burroughsian before the fact) to Raymond Chandler’s marmoreal wisecracks and Herbert Huncke’s jive. I suspect that few readers have made it all the way through the cut-up novels, but anyone dipping into them may come away humming phrases. His palpable influence on J. G. Ballard, William Gibson, and Kathy Acker is only the most obvious effect of the kind of inspiration that makes a young writer drop a book and grab a pen, wishing to emulate so sensational a sound. It’s a cold thrill. While always comic, Burroughs is rarely funny, unless you’re as tickled as he was by such recurrent delights as boys in orgasm as they are executed by hanging.

Some critics, including Miles, have tried to gussy up Burroughs’s antinomian morality as Swiftian satire. Burroughs, however, wages literary war not on perceptible real-world targets but against suggestions that anyone is responsible for anything. Though never cruel in his personal conduct, he was, in principle, exasperated with values of constraint. A little of “Nothing is true, everything is permitted” goes a long way for many readers, including me. But there’s no gainsaying a splendor as berserk as that of a Hieronymus Bosch painting. When you have read Burroughs, at whatever length suffices for you, one flank of your imagination of human possibility will be covered for good and all. ♦