Raymond Pettibon: punk with a pencil

His artwork for Black Flag and Sonic Youth helped define the punk aesthetic. Now he’s taking aim at the US government

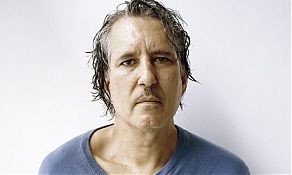

Raymond Pettibon. Photograph: Andreas Laszlo Konrath

Raymond Pettibon. Photograph: Andreas Laszlo Konrath

In the two hours that we spend talking, Raymond Pettibon’s eyes make contact with mine no more than twice. His hands tremor. The pauses between not just sentences, but individual words, stretch so long that I take to counting the seconds in my head. But these long silences come from an artist who’s made some of the worthiest noise of the last four decades. Firstly, via the literal discord of the beyond-legendary punk band Black Flag, founded by Pettibon’s brother Greg Ginn (Pettibon is a pseudonym) in Hermosa Beach, California in the late 70s; and secondly, as a hyper-verbal visual artist. His words, in other words, are worth the wait.

Pettibon didn’t last long as Black Flag’s bassist but he’s famous for coming up with the band’s name and designing its logo: those four bristling black bars, of which he’s said, modestly – or attempting to underplay their power – that “90% of motherfuckers would come up with the same scheme”. Who knows how these things are quantified, but the Black Flag logo is apparently the most tattooed symbol of all time. A factoid to which he responds, with glacial laconicism: “If not the swastika…” And then: “I don’t know which is worse sometimes… I’ve never encouraged anyone to get one. I don’t know how those things work. Some things become iconic for whatever reason and people have the logo on their arms, or wherever, but a lot of them don’t even know their music.”

Perhaps he’s wary because the iconography of the band came to transcend the music. Flea, the Red Hot Chili Peppers bassist has said: “Before I knew what Black Flag was I remember walking around Hollywood and seeing Raymond’s flyers and being like, ‘What the fuck is that?‘… Those flyers made me feel like something is going on and it’s romantic and it’s mysterious and it’s heavy and I don’t know what it is but I wanna know.” My favourite flyer is the one he made in response to frontman Henry Rollins’s request for a “fuck you” middle finger for the release of 1981 single My Rules. It is the most effete, half-hearted, wilting-in-on-itself digit in existence; an upraised finger to the idea of the power of an upraised finger. Rollins learned his lesson. “Don’t,” as he said in a recent documentary, “tell Ray what to do.” He added: “You’ll notice there’s a solid year of Black Flag flyers where it’s nothing but erect penises.”

In the decades since, Pettibon has found himself elevated from cult-hero cock-scrawler to internationally feted artist. He has that instinct for the iconic that makes his work endlessly reproducible. His cover art for Sonic Youth’s 1990 album Goo, for example, has spawned Buzzfeed lists and Tumblrs full of parodies and mash-ups, with the smoking couple re-cast as Dr Dre and Snoop (Chronic Youth), characters from Arrested Development (Sonic Bluth) and Breaking Bad’s Walt and Jesse (Sonic Meth). He’s also become an idiosyncratic and mordantly hilarious Twitter voice: “All y’all mfckrs tryyin t’correct my spellyng wrk 4 th’NSA; duh.Y’all wannt me 2 make iyt easier 4 ya pryccks.”

‘[In punk] any intellectual curiosity was discouraged. Any humour was discouraged. You had to pretend to be a moron, basically’

Sonic Youth Pettibon’s much-parodied artwork for Sonic Youth’s album Goo.

A few months back, he holed up in New York’s David Zwirner Gallery and, over several bourbon-fuelled days and nights, covered its surfaces with his work. The result was his ninth solo show, To Wit, a febrile mix of collage, scrawled aphorism and ink drawings. Grotesquely enormous penises competed for attention with elegantly scrawled and judiciously chosen snippets of literature. I found it strangely poignant. His graffitied, confrontational style is often called “cartoonish” but that incorrectly suggests a kind of burlesquing or exaggeration of the subject matter. More often than not, he’s presenting it straight. “For instance,” he says, “an atomic bomb cloud – that became 50s and 60s kitsch, you know? But the mushroom cloud isn’t an almost-quaint, kitschy part of time. In Iraq, with depleted uranium, the incidence of birth defects is huge and the number of people that were killed in Fallujah… just devastating. The use of nuclear warheads is actually being discussed, now, by people, serious people. Or people who like to call themselves serious.”

The gallery has just co-published a huge book of his political drawings, Here’s Your Irony Back. Almost all of them are caustic and brilliant. One made me laugh out loud. It’s of a marine, mooning, but as usual it’s the accompanying text that delivers the dart of humour: “This is for the liberal news media back home!” In fact they rather liked it.

He claims that most of these drawings, “are reportage, which you weren’t ever going to see from the journalistic institutions that were supposed to be doing that… the editorial pages of the Washington Post and New York Times… they’re nothing but cartoonish. Really. I’m stuck doing their reportage.” People are meant to become more conservative, or at least more politically resigned as they age. I don’t think that applies in Pettibon’s case. “I really haven’t changed,” he agrees.

We’re in his SoHo studio where drawings and cuttings are piled up on every surface. A filing cabinet offers an insight into his visual taxonomy: its labels read: “DILLINGER”, “DOLLAR”, “EARTH”, “EASTER ISL”, “ECLIPSE”. We talk about punk, and I mention the Metropolitan Museum’s Chaos To Couture show earlier this year. I tell him that I found its rooms of multi-thousand dollar designer gowns ridiculous and a bit queasy. Punk, in its US hardcore incarnation, was an anti-style movement after all. “I don’t mind it,” says Pettibon, surprisingly. “I’m suspicious of how anti-commodification [punk] was in the first place. It was more about what you can’t do than what you can do. There were restrictions. Any intellectual curiosity was discouraged. Any humour was discouraged. ‘Don’t learn another chord‘… You had to pretend to be a moron, basically. I mean, Sid Vicious was the most important intellectual figure…”

‘I just try to keep as far as possible I can away from my brother. I don’t wish him any harm.”’

Raymond Pettibon with his assistant Faren Ziello Raymond Pettibon with his assistant Faren Ziello at David Zwirner gallery in New York. Photograph: Andreas Laszlo Konrath

And that didn’t end too well. “For him, no, and for people who took that [lifestyle] up themselves. I used to discourage kids from dropping out of school or giving themselves all over to punk. I didn’t buy whole-hog into the whole thing, but at that time most people of intelligence and curiosity were likely to be in it, you know? It ruined or at least stunted a lot of people’s lives in the end.”

He insists he was never actually in Black Flag. “I did learn their songs on bass, but I got out in the nick of time and I’m glad because making art is so time-consuming. The way I do it, anyway. I mean, it would have been a disaster with Greg.” The band went through 16 different lineup changes before breaking up in 1986. Now there are two re-formed groups. One, Black Flag, consists of Greg Ginn plus Gregory Moore, Ron Reyes and Dave Klein. The other, called simply Flag, comprises Keith Morris, Chuck Dukowski, Dez Cadena, Bill Stevenson and Stephen Egerton. “Greg sued them of course,” says Pettibon. “He was always suing someone. I think he lost that case.” Ginn did indeed lose his preliminary injunction in October.

“My brother went paranoid. They turn against the people who love them the most first: parents, family, band members. He can’t be on the same stage with anyone else. Or with anyone. He wasn’t always like that, but it happens to a certain amount of people, whether it’s genetics… or probably his huge consumption of weed and psychedelics had something to do with it. I haven’t spoken to him since… probably 86.” And yet, says Pettibon, “if he knocked on the door we’d go right back to the way it was before. I have no rancour for him, because he’s living in his own reality and that can happen, potentially, to anyone and so it’s really not his fault. But the lives it affects negatively and destroys are another thing. I just try to keep as far as possible I can away from him. I don’t wish him any harm.”

He briefly reveals what he’s listening to these days (Lil B and Gucci Mane) before, somehow, the interview devolves into a game of baseball. The ball machine is positioned at one end of the studio, the end that has portraits of Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig hanging on the wall, and the batter takes their stance at the other end, beside bins rammed with vintage bats. As the balls are sent ricocheting off the ceiling, thudding into canvases, his two assistants whoop and yell. Pettibon says nothing at all.

Raymond Pettibon’s Here’s Your Irony Back is out now