Carrie Mae Weems Charts the Black Experience in Photographs

By HOLLAND COTTERJAN. 23, 2014

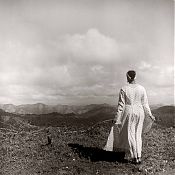

Carrie Mae Weems A 2002 self-portrait, taken in Santiago de Cuba, is in a show of her work at the Guggenheim Museum. Collection of the artist, Jack Shainman Gallery, New York

Color and class are still the great divides in American culture, and few artists have surveyed them as subtly and incisively as Carrie Mae Weems, whose traveling 30-year retrospective has arrived at the Guggenheim Museum. From its early candid family photographs, through series of pictures that track the Africa in African-America, to work that explores, over decades, what it means to be black, female and in charge of your life, it’s a ripe, questioning and beautiful show.

All the more galling, then, that the Guggenheim has cut it down to nearly half the size it was when originally organized by the Frist Center for the Visual Arts in Nashville and split it between two floors of annex galleries, making an exhibition that should have filled the main-event rotunda with her portraits, videos and installations into a secondary, niche attraction.

Ms. Weems was born in Portland, Ore., in 1953, to a family with sharecropper roots in Tennessee and Mississippi. The early civil rights years and the traumatic, nomadic 1960s were the years of her youth, and she did a lot of living fast. By her mid-20s, she had studied dance; had a child; worked in restaurants, offices and factories; spent time in Mexico, Fiji and New York; and begun a long-term commitment to grass-roots socialist politics.

In 1974, she picked up a 35-millimeter camera, and five years later, at 27, she enrolled at the California Institute of the Arts near Los Angeles to study photography. She went on from there to earn a master of fine arts degree from the University of California, San Diego, followed by a stint at Berkeley studying folklore. Zora Neale Hurston, a writer and anthropologist of black life was a hero.

Ms. Weems didn’t get much faculty notice in art school, but that seems not to have mattered. As early as 1978, she had begun the photographic series titled “Family Pictures and Stories,” which became her M.F.A. graduate show in 1984 and is the earliest work at the Guggenheim.

The series, made up of snapshotlike photographs of her family, was a product of Ms. Weems’s abiding interest in black culture and her gifts as a born storyteller. It was also a reaction to the 1965 government-issued Moynihan report that had cited family instability as the cause of the “deterioration” of African-American life.

Her response was to document, visually and verbally — she recorded an oral history to accompany the pictures — the everyday life of her own multigenerational family, one that had its share of dysfunction but was, over all, loving and mutually supportive, Ms. Weems herself being a very together product of it.

This was in no way a black-pride exercise. She understood the Moynihan report for what it was, a way to deflect attention from the reality that what the black family was up against was a long and continuing history of racism. It was that history she tackled next, first in carefully composed studio photographs of models enacting stereotypes (“Black Man Holding Watermelon”), then in still life arrangements of racist tchotchkes (Mammy and Sambo salt-and-pepper shakers), and finally, in 1989-90, in mug-shot-style portraits of African-American children.

She titled these portraits collectively “Colored People” and tinted the prints with monochromatic dyes: yellow, blue, magenta. The results were beautiful — and Ms. Weems puts a high value on formal beauty — but the colors carried complex messages. They are reminders that the range of skin colors covered by “black” is vast. But they also suggest that the social hierarchies arbitrarily built on color are operative as a kind of internalized racism among African-Americans who privilege light shades of brown skin.

The fullest development of this investigation of racism and its consequences comes in the extraordinary and now classic pictorial essay called “From Here I Saw What Happened and I Cried,” which makes as powerful an impression today as it did when it was new in 1995.

In this work, made up of 33 separate prints, all of the images are lifted from found sources, the main one being an archive of 1850 daguerreotype images of African-born black slaves in South Carolina. The portraits were commissioned by the Harvard scientist Louis Agassiz to prove his theory that blacks constituted a separate and inferior race, and the men and woman presented, stripped to the waist or naked, were intended to be evidential specimens, nothing more.

Ms. Weems adds the more. She has tinted all the pictures blood red and printed words over the images, some descriptive (“A Negroid Type”), others in the form of direct address (“You became a scientific profile”), still others passionately tender (“You became a whisper, a symbol of a mighty voyage & by the sweat of your brow you laboured for self, family & other”). The work is both an indictment of photography as enslavement, and a homage to long-dead sitters, transplanted Africans, who, under unknowable duress, gave their bodies and faces to the artist, to us, and to history.

Ms. Weems honed to this quasi-anthropological model in much of her art from the early 1990s. Her folklore study led her to explore the black Gullah communities which, because of their isolation on islands off the coast of Georgia and South Carolina, had retained strong traces of West African origins. The immersive “Sea Islands Series” that resulted, combining photographs, words and objects, is mesmerizingly atmospheric, as are two bodies of work that emerged from her travels in Africa itself.

In this series, Ms. Weems maintains the stance of omniscient, commenting observer, though this position was changing. In 1990, in what is probably her best known piece, the “Kitchen Table Series,” she introduced herself directly into the picture, playing the leading role in a carefully scripted and staged fictional narrative that unfolds in chapters over nearly two dozen photographs.

The action takes place in a narrow room neutrally furnished with a wood table and chairs; a bright lamp, which becomes a kind of interrogation light, hangs overhead. In a succession of tableaux vivants, Ms. Weems plays a contemporary Everywoman, initiating a relationship and agonizing over the direction it takes, bonding with female friends, raising kids, and finding her footing in solitude, with each phase of the story narrated in text panels.

The photographs are lush, the writing inventively colloquial, the forward pace engrossing. This is political art, but primarily in the personal-is-political sense. Issues of race and class are certainly there, but subsumed into the universal realities of life lived, daily, messy, crowded, at home.

In a sense, much of the rest of Ms. Weems’s art radiates out from this point: from home, you might say, into the world, with the artist often appearing, anonymous, back to us, in the distance, a silent witness in places where her ancestors would probably only have been present as slaves: at a 19th-century plantation house in Louisiana, for example, and among classical ruins in Rome.

A set of recent pictures by Ms. Weems that will be on view at the Studio Museum in Harlem as a supplement to the Guggenheim show make a somewhat different, but even more immediately pertinent point. Titled “The Museum Series,” it shows the artist dwarfed by the facades of international art institutions — the Louvre, the Tate Modern, and so on — which, to quote the Studio Museum news release, “affirm or reject certain histories through their collecting or display decisions.”

The Guggenheim, with its smallized, to-the-side display of Ms. Weems’s show, edges toward rejecting, even as it appears to be affirming. Instead of a full retrospective, it delivers a career sampler when it has the space and resources to do so much more.

Why didn’t it show, for example, the full “Sea Islands Series” rather than just excerpts? Why, as the last and crowning stop on the exhibition tour, didn’t it add material, fill the survey out, bring in important missing pieces like “The Hampton Project,” Ms. Weems’s haunting 2000 multimedia essay on institutional racism as it applied to both African and Native Americans?

Maybe there were problems with loans, with schedules. Whatever. Where there’s a will there’s a way. It’s a shame.

That said, the curators — Kathryn E. Delmez at the Frist Center and Jennifer Blessing and Susan Thompson at the Guggenheim — have done a solid job within their restrictions. And Ms. Weems, now 60 and much honored, is what she has always been, a superb image maker and a moral force, focused and irrepressible, and nowhere more so than in the videos that round out the show.

The short, funny 2009 fashion shout-out called “Afro-Chic” celebrates a revolutionary style while making cool-eyed note of its marketing. And in the 2003-4 compilation called “Coming Up for Air,” screened in the museum’s New Media Theater, Ms. Weems returns, with a few misfires but with a truly impressive, try-harder wisdom, to themes she started with: the rifts created by race and class, the possibility of building bridges with beauty, and the reality that the politics of living are individual, familial and universal.

“Carrie Mae Weems: Three Decades of Photography and Video” runs through May 14 at the Guggenheim Museum, 1071 Fifth Avenue, at 89th Street; 212-423-3500, guggenheim.org. “Carrie Mae Weems: The Museum Series” opens on Thursday and runs through June 29 at the Studio Museum in Harlem, 144 West 125th Street; 212-864-4500, studiomuseum.org.