December 8, 2011

A Griot for a Global Village

By HOLLAND COTTER

Across the country institutions large and small, art-specific and otherwise, are celebrating the Romare Bearden centennial year. There’s a reason for this. In Bearden’s embracing art all borders are down — between personal and universal, town and country, history and myth. Africa, Europe and the Americas too are borderless. Bearden is artist in chief of the modern cosmopolis, griot in residence of the global village. All hail.

That’s what New York City is doing in a series of exhibitions. Among those up and running there’s a succinct Bearden display at the Metropolitan Museum of Art; a more expansive one at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, a Harlem branch of the New York Public Library; and, best of all, a sparkling cross-generational Bearden shout-out at the Studio Museum in Harlem. Bearden was born in North Carolina in 1911, spent part of his childhood among the steel mills of Pittsburgh and matured as an artist in Manhattan during the Harlem Renaissance. He was fortunate in being part of a culturally alert family, in getting a multilayered education and in having talents that extended beyond art to writing (he was a notable jazz lyricist) and social organizing (he became a founder of the Studio Museum).

These talents proved useful because his art career was not smooth sailing. He paid dues of a kind all but unthinkable to artists coming out of art school today. For almost three decades, until he was in his late 50s, he held a full-time job as a case worker in the New York City Social Services Department, with, apart from occasional breaks, studio time available only at night and on weekends.

In some ways a service ethos remained an important element in his creative makeup. His generosity toward other, often younger artists was legendary. His sense of necessity, even of inevitability, as a black artist to tell an African-American story stayed firm, while he insisted on his option to explore other subjects.

And it’s important to remember that art itself, the making of it, didn’t come easy to him. He started out as a magazine cartoonist influenced by the political art of George Grosz and the Mexican muralists. At the same time he was immersing himself in a European-inflected American modernism, which led him to explore abstraction, the career-track vanguard mode of the 1940s.

He had some success with it, although he always found oil painting an intractable medium, and pure abstraction a stretch. In any case, his work wasn’t abstract enough to satisfy his New York dealer at the time, Samuel Kootz, who, determined to ride the Abstract Expressionism trend, dropped Bearden from his roster. This was in 1949, and it precipitated in Bearden a crisis of confidence that lasted for several years and gradually turned his art in other directions.

In 1950, on leave from his welfare job, he traveled in Europe under the G.I. Bill of Rights, studied philosophy and looked hard at art he found abroad. All of it. Cézanne, late Matisse cutouts, Henri Rousseau, Greek statues in the Louvre, African sculpture in the Musée de l’Homme.

The long-range effects of what he saw in Europe are instantly apparent in “Romare Bearden: The Soul of Blackness/A Centennial Tribute” at the Schomburg Center, an exhibition dominated by his grand series of illustrations for the “Odyssey” and “Iliad,” with their blend of Homeric incidents, old-master riffs and African-influenced patterning. At the same time, with the inclusion of what may well be Bearden’s earliest surviving collage, a cut-paper circus scene from around 1950, the show demonstrates how that cultural blending began to develop.

The process was long. More than a decade would pass, and a string of formal experiments, before Bearden would finally claim collage as his primary medium. The most prominent works in his first major collage show, in 1964, were photostatic enlargements of collages — the Studio Museum owns one called “Conjur Woman” — rather than the real things. Still, by then the paradigm for his art had decisively shifted.

Photographs — lifted from Life, Look, Ebony, pornographic magazines and art books — became his material. The edited images they formed were at once figurative and fractured, expressively illusive but inconclusive; painterly while being mostly paint free. They confounded notions of “black” art as being a fixed style or set of ideas and did so in an era when African-American artists were being pressured to cast their work in clear ethno-political terms.

Bearden had a strong interest in questions surrounding art and activism. In 1963 he and several other artists, anticipating that year’s march on Washington, met in weekly sessions to thrash out a role for art in the civil rights movement. Bearden believed in that role, yet in his own work he rejected hard polemics in favor of moody, jazzy storytelling, often with urban settings reflecting the city where he spent most of his time: New York.

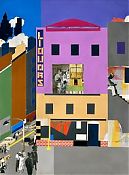

New York is the subject of “The Block,” a six-panel 1971 collage that, along with a handful of color-ink studies, makes up the Met’s “Romare Bearden (1911-1988): A Centennial Celebration.” The city block depicted is on Lenox Avenue (now also known as Malcolm X Boulevard) between West 132nd and 133rd Streets, just south of the Schomburg. The neighborhood has changed somewhat in 40 years, though Bearden’s piece still gets the basics right: motley, low-rise, abstract architecture; knots of small, specific figures (cut from copied photographs); and an overlay of generic decrepitude, conveyed here through scraped and abraded paper surfaces

What holds the eye, though, are small dramas taking place inside and outside buildings: a sidewalk funeral; a couple, seen through a window, making love; a man slumped on a stoop. And, as vivid as an exotic bird, there’s a gold-haloed Byzantine angel, its figure repeated, floating from building to building: the guardian angel of Harlem, of African-American life there.

The gritty-pretty look of the collage is very Bearden. So is its stern-sweet spirit. And both to different degrees inflect the art in “The Bearden Project,” the group show organized by Lauren Haynes, an assistant curator at the Studio Museum. For the occasion the museum commissioned 100 artists to make new work in some way inspired by Bearden. Around 50 pieces are on view (including two Beardens); others will be added as they arrive, meaning the show will change as the months go on, though it’s already impressive in its variety and imaginative scope.

A handful of artists who knew and worked with Bearden — David C. Driskell, 80; John Outterbridge, 78 — have come through with work that emulates but does not imitate him. Mr. Outterbridge’s collage “Godfather” joins African and African-American images in a thoroughly Bearden-esque manner. Mr. Driskell’s “Palm Sunday” seamlessly closes the gap between collage and painting, as Bearden intended to do.

Several midcareer artists — Kerry James Marshall, Glenn Ligon, Alison Saar — create their own dialect versions of Bearden’s complex collage language, while others (Charles Gaines, William Pope.L, and Nadine Robinson in a sound piece) acknowledge his gift for words with words of their own.

Most intriguing is to see how young artists approach a role model they can know only second or third hand, as someone else’s memory, or as a textbook image, or as an entry in (still surprisingly rare) museum holdings of African-American art. But if Bearden is now a revered fixture of the art history he loved, he’s a paragon with a lot of juice, judging by some of the responses here.

For a few artists emulation says it all. Todd Gray’s “Conjur Man” offers a homoerotic take on Bearden’s 1964 “Conjur Woman,” which is in the show, its title figure looming out of darkness like a great bandaged owl. Hank Willis Thomas and Kira Lynn Harris have both produced straightforward variations on “The Block,” Mr. Thomas in a free-standing photo montage, Ms. Harris in a chalk drawing on the walls of a gallery in the Studio Museum’s basement.

And there’s work that adds fresh elements to a Bearden lexicon. A collage by the Nigerian artist Njideka Akunyili is made up of photocopied pictures of dance clubs in Africa, a continent Bearden constantly referred to but never visited. Both Simone Leigh and the mother-daughter team Maren and Ava Hassinger, working under the name Matriarch, push Bearden’s additive aesthetic into the third dimension, Ms. Leigh with a bouquet of ceramic rosebuds made in his honor; Matriarch with a column of cardboard boxes embellished with cut paper and stacked like gifts.

I suspect Bearden would have enjoyed a QuickTime animation by Nicole Miller that features the Princeton professor Cornel West talking a fluent, jivey metaphysical funny blue streak, and sounding like Bearden collages sometimes look. And I know Bearden would have been moved to see his memory honored by a tall, abstract collage by Kamau Amu Patton, a recent Studio Museum artist in residence. Composed of torn pieces of paper darkened by different weights of rubbed-on graphite, his collage seems to catch and reflect the light in the gallery. It’s an image of blackness that’s about everything else too.

Scissors, Glue and Soul

‘THE BEARDEN PROJECT’ Through Sept. 2, Studio Museum in Harlem, 144 West 125th Street; (212) 864-4500, studiomuseum.org.

‘ROMARE BEARDEN (1911-1988): A CENTENNIAL CELEBRATION’ Through Jan. 8, Metropolitan Museum of Art; (212) 535-7710, metmuseum.org.

‘ROMARE BEARDEN: THE SOUL OF BLACKNESS/A CENTENNIAL TRIBUTE’ Through Jan. 7, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York Public Library, 515 Lenox Avenue, at 135th Street, Harlem; (212) 491-2200, nypl.org/locations/schomburg.