At home with Louise Bourgeois

Bourgeois’ New York home was an incubator for her memories and her art – and now it is being preserved. Nicholas Wroe tours the building and talks to her long-term assistant

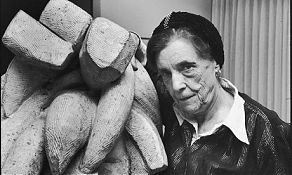

Femme maison … Louise Bourgeois with her sculpture Baroque (1970) in 1983. Photograph: Ted Thai/Time & Life Pictures/Getty

Some time in the mid-1990s, when the artist Louise Bourgeois was in her mid-80s, she asked her longtime assistant and friend, Jerry Gorovoy, to go to the top floor of her townhouse in Chelsea, New York City, and bring down some old fabric she had been storing in a closet. He returned with boxes of her old clothes – “by that point in her life, her own wardrobe had been reduced to pretty much a uniform of one or two black skirts and blouses, patent leather sneakers” – as well as those of her late mother and husband, and her children. Along with a few old napkins and tablecloths, she proceeded to transform the assorted material into series of collages, “fabric drawings” and sculptures.

“Until this time, her work was known for displaying a lot of aggression and hostility towards her father,” explains Gorovoy. “But at a certain point there was this psychological pivot towards a focus and identification with the mother. She’d been a tapestry weaver and now, instead of all the hacking and cutting of hard materials, Louise was sewing and binding and joining soft materials. In the last seven or eight years of her life, she barely mentioned the father who had so obsessed her. It was all about her mother, and, as she became increasingly frail herself, it was as if she was looking for a mother to come and take care of her.”

For Bourgeois, someone who had a lifelong feeling of abandonment, says Gorovoy, the clothes were “like a diary. They would open up the places where they had been worn, the people she had encountered, events that had happened. Personal memory was a very important part of her work and these were things that had also come into direct contact with the body. On some you could still smell her perfume. For her, this was psychically charged, raw material and while she never talked about death, I do think she wondered what would happen to all this stuff she had saved for so long and had so much meaning for her. Her attachment to these things was part of her life and she never threw anything out, so she wanted to use this raw material to make sculpture that would survive beyond her.”

Louise Bourgeois Louise Bourgeois’ Couple 1 (1996). Photograph: Christopher Burke

Bourgeois died aged 98 in 2010, and of course the work, made right up to her death, has survived her. A comprehensive survey – including examples of her fabric work – can be seen in an exhibition opening next week at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art in Edinburgh. But, intriguingly for an artist for whom the domestic space and personal possessions were so important, there are still boxes of fabric in her Chelsea home, and not just fabric.

Entering Bourgeois’ house today is a remarkable experience that seems to capture half a century of a life making art. Along with the peeling paintwork and ancient, stained sink and hob are Bourgeois’ own hairbrushes, left the mantelpiece; there are still cans of food in the cupboards and cutlery in the drawers; among hundreds of used tubes of paint are also half-empty bottles of her nail varnish. When her eyesight started to deteriorate, she dispensed with an address book and began to write important phone numbers, in huge black numbers, on the walls. In her sitting room, a fax machine is submerged under tottering piles of yellowing paper and in the corner there is a thin tower – six or seven feet high and eerily reminiscent of some of her early sculptures – made from chocolate and cookie boxes given to her as presents and topped off with a precariously placed tube of Harrods biscuits, supporting a bottle of Glenmorangie scotch.

“The way she lived, and how she thought, and the work she produced, was all seamless,” says Gorovoy. “Which is why we wanted to preserve the house as close as possible to how she left it.” Gorovoy now heads the foundation set up to administer her estate. Shortly before she died, it purchased the next-door property which will be converted into a research centre, with scholars and artists able to stay in her house and have access to her archive and diaries.

Bourgeois and her husband, the art historian Robert Goldwater, moved to Chelsea with their family in 1962. But after Goldwater’s death in 1973 their home became less a conventional domestic space than a creative incubator for Bourgeois’ memories and art. “She kept the room where her husband died, and his library,” says Gorovoy. “But she moved across the hall and never slept in that bedroom again. She got rid of her stove and just cooked what she needed on a two-burner hob. Then she got rid of the dining room table and that really was the end of domesticity, and the sitting room became a place to work and draw.”

The work and ideas she produced in this space are well-represented in the Edinburgh show. The exhibits draw on the Artist Rooms collection, established via the gift of former art dealer Anthony d’Offay’s own collection to the nation in 2008, as well as holdings from the Tate and Bourgeois’ foundation. Louise Bourgeois: A Woman Without Secrets includes her famous spiders, and her “cells” of enclosed spaces housing psychologically and sexually charged objects as well as her drawings. Although there is much later work on display, as Bourgeois consistently explained, all her subjects can trace their inspiration back to a childhood that “never lost its magic, never lost its mystery and its drama”.

Bourgeois was born on Christmas Day 1911 and brought up just outside Paris, where, as a girl, she helped in her mother’s tapestry restoration business. The key psychological event was the discovery that her father was having an affair with her English tutor, Sadie, which she saw as a betrayal by both of them, and the way he tormented and embarrassed her remained a constant source of both pain and inspiration. When the affair was revealed, Louise attempted suicide, and shortly after she nursed her increasingly frail mother until her death, when Louise was only 21, in 1932.

Louise Bourgeois Jerry Gorovoy at Bourgeois’ townhouse in Chelsea, New York. Photograph: Tim Knox

Although Bourgeois had studied maths and enrolled in the Sorbonne to read geometry, she soon abandoned science for art and became part of the pre-war avant garde scene in the city where she was taught by, among others, Fernand Léger. She opened a small gallery in Paris and, in 1938, she both met and married Goldwater. They moved to New York before the outbreak of war and adopted one son, and then had two more of their own. The couple moved in the city’s art and expat worlds and were friends with Le Corbusier and Miró as well as coming into contact with Duchamp and André Breton.

As Anthony d’Offay says, Bourgeois’ journey from tapestry to the cutting edge of modern art put her in an almost unique position as a “link between the arts and culture of the medieval world and the Renaissance and the modern world of cubism, surrealism, psychoanalysis and the postwar, post-Freudian openness about sexuality”. Throughout the postwar decades, Bourgeois made art and had solo and group shows. In her early paintings, the Femme Maison series, she depicted figures that were half woman, half house. Next came her “personages”, delicately balanced, elongated semi-abstract, semi-figurative sculptures representing the people she had known in France and America. By the 60s she was working with bronze and marble, but also less conventionally with rubber, to produce confrontationally imaginative depictions of male and female genitalia. Although she began to gain a reputation within the burgeoning feminist movement, and was collected by institutions as prestigious as Museum of Modern Art and the Whitney, it wasn’t until the 1980s that she attained any sort of profile outside the art world; she didn’t really enter the wider public consciousness until 1993, when she represented the US at the Venice Biennale.

Gorovoy first met Bourgeois in 1980 when he, as a young curator putting on a group show, included her work and she came to the gallery to strongly object to the way it was displayed. “Even then, the toll of putting on shows was too much for her,” he explains. “If you go through the diaries, you do get a sense of her frustration at not getting any traction in the art world. But an even greater cause of anxiety was that she couldn’t really handle showing the work, and so this pattern emerged of her doing the work and me doing the shows. Although, of course, I didn’t know what I was getting into: I started off working for her one afternoon a week, which became a day, and then two days; and here we are, 30-something years later.”

He says when she became better known, she was always happy to hear if someone had enjoyed a show. “But that was after the fact, and her work wasn’t really about the need to communicate; it was about the need to express what she was feeling. And as it was so self-generating and internal, it was somewhat impervious to the outside world.”

But how did she feel when her work began to attract the art world theorists? “She was conscious of what she wanted to say and, in her opinion, what her work did say. For her, it was more like a record, in that this piece of work would relate to that event or emotion. But she was also aware that other people would have different opinions. And there are many lenses on her work. You can look at it as her own psychoanalytic or therapeutic activity. But you don’t need to know any of that. It just depends on how deep you are willing to go in. At her show at the Hermitage in Russia, people didn’t know anything about her, but the work still communicated. It is a record of being in the world from a person who was physically very frail, but very unafraid to say what she wanted, even if that involved her in pain and problems.”

Bourgeois’ emotional fragility manifested itself in many ways and her behaviour could be highly erratic. She would often smash her own work in rages, or be, for apparently no reason, rude to people. “And then she’d explain that this person’s laugh reminded her of her father, or something like that.”

In later years she became agoraphobic, to add to her lifelong bouts of insomnia, and rarely left her home. “But she wasn’t a hermit,” explains Gorovoy. “She had commissions. She did interviews. But people had to come to her.” She hosted a Sunday afternoon salon where artists would come and talk about their work – she never showed her own work – and where Gorovoy’s role was to serve her guests drinks so that they would open up while she stayed sober.

“She said that people always came to pump her for information with the same questions and that she sometimes wanted to hear about other people’s love lives and traumas. When people got a bit soused, it would take the heat off her. Some people came with specific expectations, but she had a list saying that she couldn’t give anyone a job, she is not a teacher, she doesn’t accept presents, she doesn’t collect art and anything that was left would be thrown out. But if someone was applying for a grant she would write a recommendation. And she would tell them the truth about their art. This would sometimes cut straight through – people would come out crying and people would have fights. Depending on the combination of those involved, it was like group therapy.”

Giant Louise Bourgeois spider at Tate Modern, London, Britain – 03 Oct 2007 Louise Bourgeois’ Maman (1999). Photograph: Nils Jorgensen/Rex

Bourgeois would also tell people they were too pretty – “you should be a model, why don’t you stop doing art” – or too clever. “She thought that a writer had to convince you in their work, but with an artist it was just self-expression, which was more of a basic function. And, she said, if her sons had said they wanted to be artists, she would have cut their hands off, ‘but then I would have been a failure as a mother’.”

When Gorovoy first met Bourgeois, he says, he was interested in finding out what made this remarkable woman tick. “I was so attracted to the work, which to me was a mystery. But in the end I’m not sure there really is a single answer. Even now I see different things in different connections that open up her memories and her work.” He lists the major markers in her life: the death of her mother, the death of her father, her marriage, her children, the death of her husband. “But everyone has these things. So why were the repercussions in terms of what she produced so strong and fascinating? Being in her house after she has gone is still weird. She used to say that the work was more her than her physical presence. At some level that is true, because the works are like self-portraits, and the way you can sometimes feel her in the work is uncanny. And the house itself is, in a strange way, like one of her cells: it has this decrepit splendour. So while it can feel as if she’s still around, it is not the same as having her here. It was a big loss and is a big change and I still miss her.”

Artist Rooms Louise Bourgeois: A Woman Without Secrets is at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art from 26 October to 18 May 2014.

Art Weekly