Kerry James Marshall’s Painting Great America Acquired by National Gallery of Art

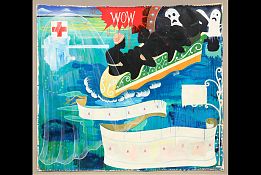

Kerry James Marshall, Great America, 1994. Acrylic and collage on canvas. National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of the Collectors Committee, 2011.

WASHINGTON, DC.- At its annual meeting in April, the Collectors Committee of the National Gallery of Art made possible the acquisition of Great America (1994) by Kerry James Marshall (b. 1955). Now on view in the East Building’s Concourse galleries, it is the Gallery’s first painting by this major midcareer artist. Marshall, a devoted student of the human figure and the history of art, draws upon the experience of African Americans to create imposing, contemporary history paintings.

“This year, the Collectors Committee’s selections included this powerful painting by Kerry James Marshall, bringing the Gallery an important work by a significant American artist,” said Earl A. Powell III, director, National Gallery of Art. “We are very grateful to the Collectors Committee, which enables the Gallery to enhance its holdings of contemporary art.”

Great America

Marshall’s mature career can be dated to 1980, when, inspired by the opening lines of Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man, he developed his signature motif of a dark, near-silhouetted figure in A Portrait of the Artist as His Former Self. Refusing both negative and positive stereotypes of black people, Marshall’s figures of “extreme blackness” operate, he explains, “right on the borderline,” forcing the viewer to find nuance and articulation within only apparently black forms. This strategy has been influential for younger artists, including Kara Walker and Glenn Ligon.

Great America is contemporaneous with Marshall’s well-known Garden Project (1994–1995), a series of paintings based on housing projects with “gardens” in their names, such as Nickerson Gardens in Watts, where he grew up. In those works, Marshall sought to convey the dignity and complexity of lives set within difficult circumstances. In Great America he re-imagines a boat ride through the haunted tunnel of an amusement park as the Middle Passage of slaves from Africa to the New World. What might in other hands be a work of heavy irony becomes instead a delicate interweaving of the histories of painting and race. The painting, which is stretched directly onto the wall, creates a screen or backdrop onto which viewers project their own associations triggered by the diaphanous yet powerful imagery.

Collecting Art by African Americans

The acquisition of Great America represents both a significant departure and a natural extension in the Gallery’s collection of works by African American artists: while the Gallery has important works from earlier eras in various media, Marshall’s work is the first truly contemporary painting to enter this collection. It joins works on paper by other African American artists of his generation, including Lorna Simpson (b. 1960), Fred Wilson (b. 1954), and Willie Cole (b. 1955). All of these artists share an interest in commenting on the African American experience through the integration of text with image.

Looking back a generation, the Gallery has important works by Sam Gilliam (b. 1933), Barkley Hendricks (b. 1945), Howardeena Pindell (b. 1943), Martin Puryear (b. 1941), and Bob Thompson (b. 1937). Alma Thomas (1891–1978) can also be placed in this artistic generation, owing to her late flowering. All of these works focus on color and abstraction, and come from a period when many African American artists were working in the mainstream, often without broaching the subject and experience of race.

Finally, the Gallery’s collection includes work by such monumental earlier figures as Romare Bearden (1911–1988), Jacob Lawrence (1917–2000), Norman Lewis (1909–1979), and James Wells (1902–1993). Charles White (1918–1979), who was Marshall’s teacher and friend at the Otis Art Institute in Los Angeles, is also represented.

“Taken together, this rich array of works represents the variety of approaches, from abstract to figurative, from expressive to documentary, pursued by African American artists throughout the 20th century,” noted Harry Cooper, curator of modern and contemporary art. “The Gallery still has much to do in building its collection to tell this story, but the foundation is surprisingly strong.”