The New York Times

December 19, 2013

The Obsessions of a Straight American Guy

By KAREN ROSENBERG

PHILADELPHIA —

The New York Times

December 19, 2013

The Obsessions of a Straight American Guy

By KAREN ROSENBERG

PHILADELPHIA — When Jason Rhoades died unexpectedly in 2006, at the age of 41, he left behind a vast and bewildering body of work: rambling, porous, performative installations that were as deliriously grandiose as anything by Dieter Roth, Paul McCarthy, Matthew Barney or Thomas Hirschhorn. Curators are still sorting it all out, to judge from “Jason Rhoades: Four Roads,” at the Institute of Contemporary Art here.

This exhibition promises to help you navigate Rhoades’s life and art, providing four “interpretive paths” that each culminate in a major installation. But the map quickly proves to be useless; all roads lead to the same place, a Gesamtkunstwerk, chaotic and overwhelming to the viewer but completely logical, one presumes, to the artist.

Each installation is simultaneously a studio and a satellite brain: a repository for the messy assemblages known as “scatter art” and for networks of information that evoke the Internet. And each installation has something to say about the stereotypical, sex-obsessed, heterosexual American male; one piece is littered with printouts of Internet pornography, another covered with neon signs that list euphemisms or the vagina.

Rhoades studied with Mr. McCarthy at U.C.L.A. and clearly picked up some of his gross-out antics, but Rhoades’s own work is less trenchant. It pushes buttons from time to time, but more often, it tickles. As the novelist and critic Chris Kraus writes in her essay in the show’s catalog, Rhoades’s work “has always been intensely physical, gleefully vulgar, ‘offensive,’ but at the same time as affectless as the demeanor of an idiot savant or made-for-TV serial killer.”

It helps that Rhoades, who started out as a painter and a ceramist, never stopped playing with color and volume; the curator Paul Schimmel, also writing in the catalog, calls Rhoades “a funny formalist, but a formalist.” In his installations, macho aggression is typically defused by little flights of visual delectation: hanging skeins of orange electrical cord, for instance, or towers of wood scraps.

That’s true even in early works like “Garage Renovation New York (Cherry Makita),” from 1993 (also seen in last winter’s “NYC 1993” exhibition at the New Museum, where it almost stole the show). Equating the artist in his studio with the weekend tinkerer in his garage, it consists of a hand-held drill hooked up to a V-8 engine and surrounded by a tool kit of tinfoil and cardboard that bring to mind the early works of Claes Oldenburg.

With its overabundance of masculinity, “Cherry Makita” seems at first like a buffoonish sendup of early-1990s identity-based art. But it also has a strong narrative pull, thanks in part to a handwritten storyboard that’s exhibited nearby; the protagonist is a paranoid cocaine dealer who starts to see himself as King Tut and the garage as his tomb. That’s a creepy but resonant idea, and it proves that Rhoades had something to add to the long history of car-based art in Los Angeles.

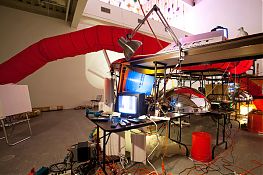

Nothing about that piece, however, prepares you for the hurly-burly of “The Creation Myth” (1998). The show’s biggest, most hectic installation, it replicates the workings of the artist’s brain with moving parts that include a model train and a sewing machine. But mental processes seem to give way to crude bodily gestures: a hay-bale spear that pokes holes in a wall, and a smoke machine that blows gaseous rings. Some of the technology is dated — note the floppy disks and the Nintendo 64 game system — but in other ways, the piece looks as relevant as ever. Its mechanized creativity seems to anticipate our age of M.R.I.s and “mindfulness.”

One of many obstacles for this show, which has been painstakingly organized and exhaustively annotated by the museum’s chief curator, Ingrid Schaffner, is that Rhoades conceived of all his installations as one big, interconnected work and often carried over components from one to the next.

For that reason, two displays in the upstairs galleries should be taken as fragments of larger projects. The steel tubes in “Sutter’s Mill” (2000), a structure based on the sawmills of the California Gold Rush, come from Rhoades’s magnum opus: a five-mile-long installation called “Perfect World,” exhibited in Germany in 1999.

And the installation “Untitled (from My Madinah: In pursuit of my ermitage …)” (2004/2013) is a rather tame sampling of a provocative series of installations and performances, the title of which can’t be repeated here. It might ruffle a few feathers, with a thesaurus-worth of slang words for the female anatomy and its exoticized, souklike interior (the equivalent, perhaps, to the man cave of “Cherry Makita.”)

It’s hard to describe this piece without making it sound like a bad joke. Suffice it to say that its various insensitivities — to gender, to culture, to religion — are complicated (though never eradicated) by a playful sense of language and space, and by our own complicity as viewers who enter and immerse ourselves in the inanity. (At the show, we’re invited to take off our shoes and examine the neon canopy from a patchwork carpet of colorful towels.)

Another mitigating factor is the cult of Rhoades himself, as revealed in video interviews with curators and other artists. Describing installations like “The Creation Myth,” he hooks you with his endless detours and digressions while somehow keeping up a smarmily professional, Koonsian facade. As Ms. Schaffner observes in her catalog essay: “It’s this constant narrative flow that invisibly holds Rhoades’s production together. As he assembled thoughts in his mind, so did he organize objects in space, and like a good storyteller, he never ‘told’ an installation exactly the same way twice.”

“Jason Rhoades: Four Rhoades,” is, therefore, a circus missing its ringmaster. That’s a sad circumstance, but in the long run, it may help us to see his work more clearly. Art, Rhoades once said, “should shut you down; it should make you give up something.” The reverent, even hagiographic tone of this show, even seven years after his death, suggests that critics and curators have given up enough already — including, sometimes, their own interpretive power.

“Jason Rhoades: Four Roads” runs through Dec. 29 at the Institute of Contemporary Art, University of Pennsylvania, 118 South 36th Street, Philadelphia; 215-898-7108, icaphila.org.

More in Art & Design (9 of 52 articles)

Art-Scene Glimpses, Lost Then Found

Read More »

This exhibition promises to help you navigate Rhoades’s life and art, providing four “interpretive paths” that each culminate in a major installation. But the map quickly proves to be useless; all roads lead to the same place, a Gesamtkunstwerk, chaotic and overwhelming to the viewer but completely logical, one presumes, to the artist.

Each installation is simultaneously a studio and a satellite brain: a repository for the messy assemblages known as “scatter art” and for networks of information that evoke the Internet. And each installation has something to say about the stereotypical, sex-obsessed, heterosexual American male; one piece is littered with printouts of Internet pornography, another covered with neon signs that list euphemisms or the vagina.

Rhoades studied with Mr. McCarthy at U.C.L.A. and clearly picked up some of his gross-out antics, but Rhoades’s own work is less trenchant. It pushes buttons from time to time, but more often, it tickles. As the novelist and critic Chris Kraus writes in her essay in the show’s catalog, Rhoades’s work “has always been intensely physical, gleefully vulgar, ‘offensive,’ but at the same time as affectless as the demeanor of an idiot savant or made-for-TV serial killer.”

It helps that Rhoades, who started out as a painter and a ceramist, never stopped playing with color and volume; the curator Paul Schimmel, also writing in the catalog, calls Rhoades “a funny formalist, but a formalist.” In his installations, macho aggression is typically defused by little flights of visual delectation: hanging skeins of orange electrical cord, for instance, or towers of wood scraps.

That’s true even in early works like “Garage Renovation New York (Cherry Makita),” from 1993 (also seen in last winter’s “NYC 1993” exhibition at the New Museum, where it almost stole the show). Equating the artist in his studio with the weekend tinkerer in his garage, it consists of a hand-held drill hooked up to a V-8 engine and surrounded by a tool kit of tinfoil and cardboard that bring to mind the early works of Claes Oldenburg.

With its overabundance of masculinity, “Cherry Makita” seems at first like a buffoonish sendup of early-1990s identity-based art. But it also has a strong narrative pull, thanks in part to a handwritten storyboard that’s exhibited nearby; the protagonist is a paranoid cocaine dealer who starts to see himself as King Tut and the garage as his tomb. That’s a creepy but resonant idea, and it proves that Rhoades had something to add to the long history of car-based art in Los Angeles.

Nothing about that piece, however, prepares you for the hurly-burly of “The Creation Myth” (1998). The show’s biggest, most hectic installation, it replicates the workings of the artist’s brain with moving parts that include a model train and a sewing machine. But mental processes seem to give way to crude bodily gestures: a hay-bale spear that pokes holes in a wall, and a smoke machine that blows gaseous rings. Some of the technology is dated — note the floppy disks and the Nintendo 64 game system — but in other ways, the piece looks as relevant as ever. Its mechanized creativity seems to anticipate our age of M.R.I.s and “mindfulness.”

One of many obstacles for this show, which has been painstakingly organized and exhaustively annotated by the museum’s chief curator, Ingrid Schaffner, is that Rhoades conceived of all his installations as one big, interconnected work and often carried over components from one to the next.

For that reason, two displays in the upstairs galleries should be taken as fragments of larger projects. The steel tubes in “Sutter’s Mill” (2000), a structure based on the sawmills of the California Gold Rush, come from Rhoades’s magnum opus: a five-mile-long installation called “Perfect World,” exhibited in Germany in 1999.

And the installation “Untitled (from My Madinah: In pursuit of my ermitage …)” (2004/2013) is a rather tame sampling of a provocative series of installations and performances, the title of which can’t be repeated here. It might ruffle a few feathers, with a thesaurus-worth of slang words for the female anatomy and its exoticized, souklike interior (the equivalent, perhaps, to the man cave of “Cherry Makita.”)

It’s hard to describe this piece without making it sound like a bad joke. Suffice it to say that its various insensitivities — to gender, to culture, to religion — are complicated (though never eradicated) by a playful sense of language and space, and by our own complicity as viewers who enter and immerse ourselves in the inanity. (At the show, we’re invited to take off our shoes and examine the neon canopy from a patchwork carpet of colorful towels.)

Another mitigating factor is the cult of Rhoades himself, as revealed in video interviews with curators and other artists. Describing installations like “The Creation Myth,” he hooks you with his endless detours and digressions while somehow keeping up a smarmily professional, Koonsian facade. As Ms. Schaffner observes in her catalog essay: “It’s this constant narrative flow that invisibly holds Rhoades’s production together. As he assembled thoughts in his mind, so did he organize objects in space, and like a good storyteller, he never ‘told’ an installation exactly the same way twice.”

“Jason Rhoades: Four Rhoades,” is, therefore, a circus missing its ringmaster. That’s a sad circumstance, but in the long run, it may help us to see his work more clearly. Art, Rhoades once said, “should shut you down; it should make you give up something.” The reverent, even hagiographic tone of this show, even seven years after his death, suggests that critics and curators have given up enough already — including, sometimes, their own interpretive power.

“Jason Rhoades: Four Roads” runs through Dec. 29 at the Institute of Contemporary Art, University of Pennsylvania, 118 South 36th Street, Philadelphia; 215-898-7108, icaphila.org.

More in Art & Design (9 of 52 articles)

Art-Scene Glimpses, Lost Then Found

Read More »