The New York Times

December 26, 2013

Islamic World Through Women’s Eyes

By VICKI GOLDBERG

BOSTON — Middle Eastern women, supposedly powerless and oppressed behind walls and veils, are in fact a force in both society and the arts. They played a major role in the Arab Spring and continue to do so in the flourishing regional art scene — specifically in photography — which is alive and very well indeed. Some Middle Eastern photographers have taken their cameras to the barricades, physical ones and those less obvious, like the barriers erected by stereotypes, which they remain determined to defy. The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, takes note in “She Who Tells a Story: Women Photographers From Iran and the Arab World,” an ambitious and revealing exhibition of work by 12 women, some internationally known.

The curator, Kristen Gresh, says in the catalog that this show, which runs through Jan. 12, was intended to explore “the dualities of the visible and invisible, the permissible and forbidden, the spoken and the silent, and the prosaic and the horrific.” These approximately 100 photographs and two videos generally respond to that intention and open a wide window on what preoccupies women in regions that are read about here more often in news articles about riots and refugees. At times, the ideas in this show count more than the images, which range in quality from remarkable and convincing to the merely derivative in some cases.

In the Middle East, it hasn’t always been easy or considered respectable for women to photograph. Boushra Almutawakel, born in Yemen, recalled that a man once asked her what she did; when she replied that she was a photographer, he said sweetly, “It’s nice to have a hobby.” She was nervous about her first show, partly because it included pictures of herself, but only later did her mother voice disapproval: “Who shows pictures of herself?” She answered, “Mama, they’re art, they’re in a museum,” to which her mother replied, “Who sells pictures of herself?”

Iran poses particular difficulties to photojournalists, both male and female. Shadi Ghadirian, from Iran, said in a video that in her country a female photographer is a potential traitor. Many colleagues have been detained and imprisoned, and some have never returned. Newsha Tavakolian, an Iranian who has photographed for The New York Times, said in an interview, “We have a red line.” Where is it? “I don’t know. No one knows where it is.” Then, with a shrug, she added, “Everyone knows.”

Iranian photojournalists need the Information Ministry’s permission to photograph. Ms. Tavakolian’s card has been revoked more than once, so she finally shifted to art photography. Photography (and other art forms) thrive in Iran, as do cellphones clicking along the sidewalks. Gohar Dashti, also Iranian, said that, after the 1997 election, a hundred galleries sprang up, usually in some third-floor private apartment, where a hundred people typically jam into at openings.

The authorities, Ms. Tavakolian said, generally miss messages that gallerygoers decipher easily. Western viewers may miss the messages, too, though those may be more meaningful than the aesthetics are. A series by Ms. Tavakolian, bewildering at first, features women with closed eyes, moving mouths and evident emotion — a silent performance. Only the wall text explains that these are professional singers and the series a modest protest against conservative restrictions that forbid women from singing in public, effectively silencing them.

Other images are a bit too cryptic. The Egyptian women riding the Cairo subway in Rana El Nemr’s photographs certainly look depressed (as do some riders on American subways), but no photograph musters the complexity to illustrate Ms. El Nemr’s statement in the catalog that her subjects are vulnerable to illnesses caused by indifference and religious intolerance “and transmitted to the rest of Egyptian and Arab society and the world.”

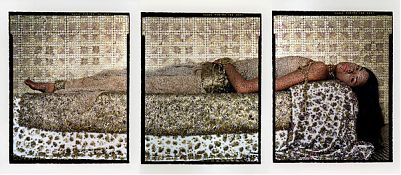

One recurrent reference is the ubiquitous drumbeat of war that accompanies the march of everyday life. Some approaches are rather obvious, though irony has its appeal in Ms. Dashti’s images of a couple hanging laundry on barbed wire or wearing bridal regalia in a burned-out car in the desert. The Moroccan Lalla Essaydi’s multipart image of an odalisque wearing golden jewelry in a golden-tiled room shifts radically when you realize that all the gold is bullet casings.

The theme pursued with the most energy and invention is the resentment of stereotyping, that sly and effective means of erasing individuality. One example is the omnipresent Western notion of the Middle Eastern woman as veiled, exotic, erotic, anonymous, suppressed and powerless, yet threatening. More than one photographer here adamantly insists on another identity.

Ms. Almutawakel, angry that Arabs were viewed in the West as evil after Sept. 11, veiled her head with an American flag. That targeted that stereotype. More prevalent in the show is the Western fixation on the veil, a garment that stirs controversy even in the Middle East. Ms. Almutawakel’s series “Mother, Daughter, Doll” at first portrays the three figures in the various garments, colors and veiling available to women, followed by several pictures of them clad entirely in black, progressively muffled up to the eyes. In this critique of extremism, Ms. Almutawakel said that for little girls to be covered to this extent is not about religion but control.

Ms. Ghadirian photographed a woman wearing a hijab, which covers the head and chest, in a 19th-century studio setting but holding contemporary objects like a Pepsi can and a boombox, both of which were officially banned for years in Iran. Thus she acknowledges the changes history brings to life and even to photography, sometimes in small doses.

Jananne Al-Ani, half Irish, half Iraqi, dwells on the veil’s complexity: She photographed five women whose appearances vary from entirely veiled to heads uncovered, one with knees and thighs exposed; she then rephotographed them, changing the veiled women to unveiled and vice versa. Ms. Al-Ani has studied 19th-century Orientalist paintings like those of Delacroix and Gérôme and maintains that these were total fictions that photographers back then accepted and restaged. Photographs made in the Middle East for the European market, she said during a panel discussion at the museum, played to the Western fantasy of unveiling the veiled woman. She projected an early photograph of a woman with her face covered except for the eyes, but her gown is slit twice to expose her bare breasts — the veil imagined as a wily cover-up for a voluptuous sexuality.

In Ms. Al-Ani’s own photographs, she rejects another fiction, that of the “veiled” landscape seen in Orientalist depictions of Middle Eastern deserts as empty, blank, lifeless, unoccupied. She says this idea still echoes, citing the 1991 gulf war, when the news media focused on aerial and satellite images of desolate reaches of sand. Her own aerial photographs reveal the traces of ancient buildings: Bodies have disappeared but human beings have left their mark.

Feminine stereotypes are not the exclusive property of the Middle East. Queen Noor of Jordan, who introduced the panel at the museum, pointed out that Bella Abzug, the feminist leader and former congresswoman, wore hats to look like a professional, so that her male colleagues would stop asking her to get them coffee.

One of the results of stereotypes, especially on the part of Westerners viewing the Middle East, is to obscure and smother individuality. But 12 women from Iran and Arab countries — individuals all — insist that photography, despite its limitations, can still demolish the fictions that linger in our minds.

“She Who Tells a Story: Women Photographers From Iran and the Arab World” continues through Jan. 12, at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; 617-267-9300, mfa.org