NON-WESTERN ART DISCOURS

Don’t say ethnic or tribal: the word is ‘customary’

The Asia Pacific Triennial pulls in Papua New Guinea and West Asia

By Anna Somers Cocks. News, Issue 243, February 2012

Published online: 03 January 2013

Australia was perhaps uniquely prepared 20 years ago to look at art from other cultures on its own terms. It was in December 1992 that Prime Minister Paul Keating made what is now considered to be one of the greatest speeches of Australia’s history, in which he recognised the damage Western settlers had done to the Aboriginal people. “We committed the murders. We took the children from their mothers. We practised discrimination and exclusion. It was our ignorance and our prejudice.”

Right-thinking Australians have become acutely sensitive to the need not to view the West as the sole arbiter of civilisation and culture. Serota so much admired the way Qagoma has put this message into practice that four years ago he sent a group of curators there to learn their method, which can be summed up as “collective effort”, both inside the gallery and out in the field. Raffel says that they use their vast network of contacts—artists, writers, curators, thinkers, architects, anyone involved in the material culture of today—throughout the two-thirds of the world that they cover in the APTs.

For this year’s star billing, Papua New Guinea, they have collaborated with the artists and the architect Martin Fowler, who grew up there and has designed Papua New Guinea’s museum.

The first thing you see when you go into the Gallery of Modern Art, where most of APT7 is located, is a huge painted gable of the kind found on ritual buildings in East Sepik. Anyone can enjoy its splendid decorative qualities, but all kinds of ritual meanings are also bound up in it, and these have been respected by the gallery. We are told that the senior artist of the team that came to Brisbane to paint it said the big spirit man Puti, represented at the top of the gable, gave him permission to make this spirit house in Australia and to use synthetic polymer paints.

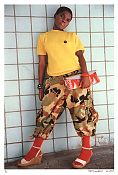

One may smile, but it is in earnest. There are also wonderfully decorative Papua New Guinean full-body masks. The gallery has a good word for this art: “customary”, that is, the product of customs, which is much better than “ethnic” or, worse still, “tribal”, epithets that consign such work to the anthropological compound. A stimulating essay in the catalogue is about how customary art is not static, as we tend to think, but evolves according to criteria of its own and in response to outside events. The message is: we have a lot to learn.

Thoughtful connections

The New Zealand artist Graham Fletcher adds his comment in paintings that show Habitat-style living rooms with “tribal art” as tasteful interior decoration, while Rina Banerjee, Indian-born and New York-based, makes wild montages of feathers, horns, teeth and lightbulbs that look as though they might be customary art until you look closer. For one of the enjoyable aspects of the triennial is that its curators really curate. The visitor feels guided. Unlike most biennials, which are usually a pretty random assemblage of works grouped under some nebulous title, this exhibition is worked on for the full three years between editions; the connections are made, in both the art and the excellent labelling (the labels for children are particularly good).

There are works from Indonesia, China, Vietnam, India, Pakistan, Japan, Turkey, Thailand, Australia, South Korea, Iran, the Philippines and, for the first time, the Middle East and Central Asia. These are all self-consciously works of art in the Western meaning of the word, but so many of them are about cultures contemplating each other that they are not incongruous in the company of the customary art, which challenges us in this thoughtful environment to reflect precisely on how little we understand each other.

The APT is fully funded by the government of Queensland, Qagoma and sponsors, the main one this year being the energy company Santos. It does not need help from dealers in paying for the logistics, so another very attractive aspect of this important exhibition is that nowhere do you get the sense that it is connected with the art market. You feel this freedom in its combined rigour and originality.