The New York Times

July 25, 2012

’70s Portrait of Harlem, Gathered for Today

By GWENDA BLAIR

ONE day in early 1969, a 16-year-old black high school student from Queens named David Smikle decided to go to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, which he had never visited. He’d heard on the radio that people were upset about an exhibition there, “Harlem on My Mind,” and he wanted a firsthand look.

To his disappointment, no protesters were outside the museum, which was under fire for excluding work by black artists in its portrayal of Harlem. But inside he saw something that left an indelible mark: walls plastered with blown-up photographs of ordinary black people that museumgoers seemed to find compelling enough to stand before and examine.

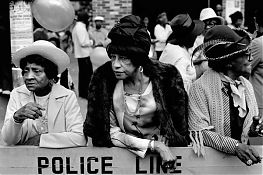

Ten years later, having changed his name to Dawoud Bey and studied photography at the School of Visual Arts, he made his debut with a solo show at the Studio Museum in Harlem. Called “Harlem USA,” it consisted of 25 black-and-white photographs of neighborhood residents, like military veterans in a marching band and older women on their way to church.

Mr. Bey, who now lives in Chicago and teaches photography at Columbia College there, became a widely acclaimed portrait photographer, known for conveying a self-awareness and introspection in his subjects. His work has been shown across the United States and Europe and is in the permanent collections of the Museum of Modern Art, the Whitney Museum of American Art and the Brooklyn Museum.

This summer at the Art Institute of Chicago, for the first time since the 1979 Studio Museum show, his Harlem series is being exhibited in its entirety. The Art Institute set up a special fund-raising drive to purchase prints, mostly vintage, of the original series (for a price Mr. Bey described as in “the low six figures”) and is also presenting other works in its collection by photography pioneers, including James Van Der Zee, Irving Penn and Roy DeCarava, all of whom influenced Mr. Bey.

On a recent afternoon Mr. Bey, 58, visited the Art Institute’s exhibition and talked about the tie between his photos and “Harlem on My Mind.”

“At that time,” he said, “I was walking around with a box camera I’d inherited from my godfather because I thought it looked cool. But I didn’t know what to do with it. The show at the Met stayed with me, got me thinking.”

He began going to other museums and galleries and looking at the photographs of innovators from earlier in the century, like Walker Evans and Henri Cartier-Bresson. “Their work gave a sense of what I wanted to do and what I didn’t want to do,” he said. “It wasn’t just illustrative. It was subjective and interpretive. These photos began to point to a direction, to show that photos of ordinary people, evocatively described, could be meaningful.”

By the mid-’70s he was using a single-lens reflex camera and had started taking the Harlem street photographs that would eventually make up the Studio Museum show. Unlike most street photographers he worked slowly, taking few pictures and making an average of only three exposures of each subject.

“I wanted to show people living their lives,” he said. “But first I had to learn how to insert myself into their social space and make it seem natural.” The first time he felt he succeeded was in a photograph, included in “Harlem USA,” that shows a middle-aged man in a black overcoat and bowler hat outside a brick row house.

As soon as he saw the man, Mr. Bey recalled, he wanted to take his picture. But the man was talking to other people, so Mr. Bey walked by. “Then I kicked myself and turned around,” he said. This time he locked eyes with his would-be subject and asked if he could take a photograph. The man said yes. When Mr. Bey asked him to do what he’d been doing before, the man leaned against the railing and cupped his left hand, providing what Mr. Bey calls a “grace note.”

“I had figured out the geometry of the space and the interlocking shapes,” Mr. Bey said. “But I needed the quirky little gestures of behavior that mark the individual, the stuff you can’t make up. I needed a way to create a momentary connection that would leave viewers feeling they knew this person.”

Such grace notes appear again and again in Mr. Bey’s photographs. One of the most striking in the Harlem series is in the photograph on the cover of the exhibition catalog. It features a boy wearing sunglasses who stands on his tiptoes so that he can lean with exaggerated nonchalance against a wooden barricade outside a movie theater.

In the more than three decades since the Studio Museum show Mr. Bey has continued to explore African-American subjects and, more recently, adolescents of diverse backgrounds. In the process he has switched from black and white to color, moved to large-format cameras and shifted between street and studio. This evolution is reflected in another Chicago exhibition, “Dawoud Bey: Picturing People,” a career retrospective that was at the Renaissance Society, a contemporary art museum on the University of Chicago campus from May to mid-July and will travel around the country next year.

For the critic Arthur Danto, who wrote an essay for the “Picturing People” catalog at the Renaissance Society, an underlying humanism unifies all of Mr. Bey’s work. “There’s such a quality of clarity and sympathy and understanding,” Mr. Danto said by telephone from New York. “People sometimes talk about his photos having some of the same quality as Rembrandt.”

Mr. Bey’s latest project is a series of large-format photographs of people who live in the same area but don’t know each other. For each work he selects two subjects, usually a man and a woman, often of different ages. Then he places them together in their community in settings like a long hallway or a library reading room that provide a geometrically distinctive background.

“I step back, fiddle with the camera, do something so they have a chance to get comfortable,” he said. “Then I watch for the moment — the hand across the knee, the elbow leaning on the chair back — that shows us who these people are and how the narrative of the space and the narrative of two individuals interact.”

What may distinguish Mr. Bey most, however, is less the geometric precision with which he presents space in his portraits than what David Travis, former curator of photography at the Art Institute, refers to as Mr. Bey’s “moral compass.”

“He wants to discover things about people, not stop at the surface but really get under the skin,” Mr. Travis said. But unlike Richard Avedon, who often had a strobe light go off when people were unprepared, or Diane Arbus, who once said that taking a photograph was “like tiptoeing into the kitchen late at night and stealing Oreo cookies,” Mr. Bey insists that the process be collaborative.

“Dawoud believes the sitters have a voice, and he won’t steal anything they don’t want shown,” Mr. Travis said. “He’s very considerate about never really taking a face the sitter didn’t mean to give up. He’s not a trespasser.”