The Ins and Outs of Contemporary Mexican Art, in Texas

by Erin Joyce on November 27, 2013

FORT WORTH, Texas — It often seems like the world is made up of pairs: Christo and Jean Claude, Hall and Oates, peanut butter and jelly. Yet some things that seem like they’d fit well together have not cohabitated as one would assume. Take contemporary Mexican art and the state of Texas. They seem like a natural pairing, a kind of cultural chips and salsa, given that the state is so heavily influenced, and bordered by, Mexico. But in reality, a major exhibition of contemporary Mexican art has not taken place in Texas since … well, a very long time. And never in North Texas.

At the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, they’re trying to change that. According to curator Andrea Karnes, this is the first major exhibition of contemporary Mexican art anywhere in the US in over a decade. Karnes set out to bring art from Mexico to Texas in a way that’s never been done before, displaying a complex network of works and artists in a museum setting. México Inside Out: Themes in Art Since 1990 marks the first time many of the artists represented in the installation have shown in the Lone Star State. Occupying a majority of the museum’s second floor, the exhibition features over 65 works by 23 artists of either Mexican origin or based in Mexico. The show is large, encompassing painting, sculptural installation, video, drawing, photography, and the list goes on.

Broken up into three thematic veins, the exhibition covers ideas of constructing contemporary monuments, interrogating systems of power, and magnifying the everyday. This fragmentation of the works is necessary, as the exhibition would easily swallow the viewer up otherwise; even the pieces we get are by no means bite sized.

At the top of the stairs, a video work by British-born, Mexico City–based artist Melanie Smith greets visitors and sets the stage for the exhibition to come. The eerie, black-and-white single-channel film displays haunting images of cityscapes taken from an aerial perspective. It serves as a singular manifestation of the exhibition — an overview of the environment of contemporary Mexico. The first gallery offers an entire room of Gabriel Orozco, featuring photographs, prints, and the artist’s famous ping-pong table sculpture. The table invites participation, as visitors are welcome to play the game; however, the original conditions of the table have been subverted by the artist, who’s dissected it into quarters and arranging them around a small pond. The hindrance introduced by the water component calls to mind illegal border crossings, transnationalism, and the element of fear.

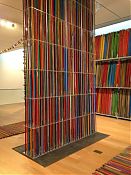

Thomas Glassford, “Broomsticks” (2013), 7,000 wood broomsticks, library shelves

In gallery two, a massive work by Thomas Glassford stares you in the face. A sculptural installation featuring over 7,000 broomstick handles collected from various locations in Mexico, the piece addresses one of the show’s primary themes: monumentalizing the everyday. The site-specific work by Glassford, a Texas native now based in Mexico, takes the tropes of the readymade and found objects, and applies them to racial stigmas surrounding Latinos both in Mexico and in the United States. The broomsticks allude to stereotypical professions that Latinos fill, such as janitors, maids, and busboys. But Glassford has circumvented the functionality of the broomsticks by removing their bristles and using the poles as visually stimulating objects. He elevates the cleaning and custodial arts by placing them within the context of a modern art museum. He uses the institutions’ canonical position to validate them.

Pushing deeper into the museum, you come across an oppressive work by Artemio. The Mexican installation artist known for his cheeky blend of pop culture pastiche and social commentary has created a work that pushes you to the emotional edge. Occupying a large portion of the gallery space is a floor-to-ceiling mound of dirt. Consisting of 28,000 kilos of dirt imported from Mexico, the piece is a commentary on the horrific violence against women that has grown exponentially under the influence of drug cartels. The weight of the dirt is equal to the weight of 450 dead bodies, as mentioned in the title: ”Untitled (Portrait of 450 Murdered Women in Ciudad Juárez)/Sin Titulo (Retrato de 450 mujeres asesinadas en Ciudad Juárez).” The mound of earth is immensely poignant; it memorializes these women, returning their bodies and memories to dust.

México Inside Out has a strong contingent of video and time-based media work. Among those is Yoshua Okón’s “Orillese a la Orilla” (1999–2000), a three-channel film installation that features policemen from Mexico City whom Okon invited into his studio. The film is a series of dramatized encounters between civilians and the officers, with varying degrees of conflict. It explores the tension of hybridity, between fact and fiction, between document and dramatization.

The way the films are mounted in the exhibition is quite imposing, too: each channel is projected in a singular small room, occupying the entire back wall. The character of the policeman towers over you, crushing you under the weight of this manifestation of “power,” this figure of authority you’re not sure you can trust. Questions of the truth of the moving image also come into play: What’s real here? How much influence did the artist have over the behavior of the officers? What constructs of narrative are present? Okón’s work implicates the artist, the legal system, and even, to some degree, cultural institutions as agents of dissemination.

México Inside Out is a powerful and impactful exhibition. At times, it presents overwhelming amounts of information, which can confound the viewing experience, making it difficult to focus on one work in particular. The gallery rooms often feel chaotic, discombobulated, and uneasy, but perhaps that’s the point. Mexico is going through tumult, and it’s refracted through the prism of the contemporary art world and the museum. At a time when political instability, violence, and cultural stereotyping are inordinately high on both sides of the border, México Inside Out functions as both a mirror and a microscope. It forces us to look not only at what’s going on around us, but also what’s going on within.

México Inside Out: Themes in Art Since 1990 continues at the Modern Art Museum of Forth Worth (3200 Darnell Street, Forth Worth, Texas) through January 5, 2014.