New David Hockney exhibition: From Gandhi to gay love

Hockney has always had a rebellious streak, as Adrian Hamilton discovers at a show spanning his 60-year career

Adrian Hamilton

Sunday, 9 February 2014

Of all the artists working today David Hockney is by far the most assiduous in his respect for the traditions of art and his concern to push it to new limits. However modern his subject and experimental his style, there is always the sense that here is a painter who feels himself part of a history that he reveres with past masters whom he wishes to emulate.

What you can say of his paintings and drawings you can also say of his prints, even more so as he has wrestled and developed the techniques of the craft, as a comprehensive show of his talent as a print-maker at the Dulwich Picture Gallery splendidly shows.

He started etching at the Royal College of Art. The story goes that he took it up because, short of money for paints, he was told that the print-making rooms gave out their materials for free. He was reputedly taught how to etch in a 15-minute lesson from a fellow student.

Like most stories that have accrued round this bluff, obstinate artist, this one needs to be taken with a good dose of Yorkshire salt. He had in fact already studied lithography at Bradford College of Art. Etching, where the lines are drawn by incising the wax covering of the plate, is easy enough to grasp at its most basic level. It is the art of shading and depicting textures which is difficult.

What the story does show is how confident a graphic artist he was right from the start. What it also shows is how cheeky he was in his approach to work. The first print on show is entitled Myself and My Heroes with pictures of the poet Walt Whitman and the Indian proponent of passive resistance, Mahatma Gandhi, each with quotes from them. Hockney himself appears on the side, presented in the manner of a donor in a mediaeval diptych, and simply inscribed “I am 21 years old and wear glasses”.

Nearby is the print he made when told that he wouldn’t be awarded a degree after he refused to write an essay. He declared the exercise was pointless as he came to study art not writing. So he produced instead an etching of a faux diploma satirising the heads of the college crushing the bent figures of the five refuseniks beneath. It’s witty but also done with great panache.

p40-hockney-2.jpg It is now 60 years since Hockney made his first print when studying for a design diploma at Bradford College at Art: a lithographic portrait of himself done with a nod to Vuillard in its concentration of pattern and wallpaper but with a youthful assertion of self as he sits staring straight at the viewer through round glasses, his arms folded and his hair plastered down.

Dulwich divides its six rooms into half, the first part devoted to his etchings and the second to his more colourful and expansive lithographs. It makes sense. For what you lose in sequence you gain in the revelation of how he applied himself to the possibilities of the medium.

The etchings start off with works quite similar in tone and composition from the drawings and paintings he was doing at the same time. There is the same use of words with image, the brushed ink flows and cartoon characters that formed his Pop art style of the period. He tried, with increasing confidence, to add colour (usually red) but never seemed entirely happy at the result.

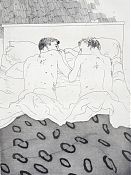

It is with his series illustrating the poems of Constantine Cavafy and the stories of the Brothers Grimm as well as the portraits of the mid-Sixties that you really feel him finding himself as a print-maker. He abandons colour and texture for line. He also feels rising confidence in coming out as gay. The etchings of the naked male couples from the Cavafy series of 1966 are full of tenderness and delicacy, the figures drawn in fine lines and little tone. As interesting are the plates he rejected, not least because it’s so difficult to figure out why he rejected them.

The Grimm series from 1969 is more ambitious in its etching of textures, their literary interpretations (the enchantress of the Rapunzel story is pictured as an old hag too ugly and too worn to have a child of her own) and in the references to the images of other artists. With his portraits of the Seventies and his flower still lifes he becomes much more probing in his use of hard and soft ground etching and aquatint, particularly after his visit to Picasso’s printers in Paris, who had developed a way of allowing the artist to use colour with greater accuracy.

p40-hockney-3.jpg When it came to lithography – a process that uses the opposite attractions of water and grease to produce plates – Hockney, one of the great colourists of contemporary painting, is more experimental, artistically and technically.

Preferring to use friends and those whom he knows well rather than commissioned portraits, he’s extraordinarily good at capturing presence in his sitters. A full-length portrait of his long-standing friend, Celia Birtwell, has her in a long dress of delicately washed black, while Henry Geldzahler, the driving force of the Museum of Modern Art in New York, is shown poised at a richly covered table, his hands clasped as he stares over a potted plant.

The lithograph portraits are in many ways an extension of his pencil, crayon and ink drawings of the period, immensely subtle but confined by the print process, except when he tries (and succeeds) in reproducing the effect of rapid brush strokes as in Big Celia Print 2 from 1981. His lithographs of flowers are much nearer his watercolours, quite static in composition but delicate in colour and lines.

His landscapes in contrast took a dramatic turn with the development by his printer, Tyler Graphics, of a “Mylar Layering system” by which the artist could draw separate colours on any number of plastic sheets and then have them superimposed on each other to produce a final print.

Already experimenting in paint with fractured compositions after being struck how, in Chinese art, a scene was viewed from multiple viewpoints, Hockney now used the new process in the mid-Eighties to make highly coloured prints of the inside courtyard of a Mexican hotel he’d been stuck in and also Cubist portraits in which he deepened the effect by putting layer on layer of Mylar sheets of the same colour.

p40-hockney-4.jpg The Dulwich exhibition was originally intended as a companion piece for a major retrospective of Hockney in London. The artist typically chose instead to burst forth with a whole new series of monumental landscapes of his native Yorkshire at the Royal Academy, including a room devoted to inkjet-printed enlargements of his digital iPad sketches.

Dulwich ends with two of his recent prints from computer drawings together with a group of earlier prints made on a copying machine. They puzzled the critics, as indeed the public, as to whether they were genuine artworks or merely the products of machines. Hockney, clearly delighted with the tease, is in no doubt. However mechanical the printing, the act of photocopying a drawing, sometimes several times over, to deepen its colours, or of manipulating a computer tablet, is an act of creation.

Of course, he’s right. After a century of Dadaism and Arte Povere, the question of what is true art and what manufactured product has long been exhausted. The issue is whether Hockney is merely playing with technology or using it for a purpose. Of the brilliance of effect in Hockney’s prints there can be little doubt. Some of his series – the Cafavy etchings, the Weather Series and some of the portraits in both print forms – must rank as among the finest print works produced over the past century. But in other works you feel the medium is the message at the cost of content.

A rewarding exhibition which firmly establishes, if it was needed, Hockney as one of the most innovative and imaginative print-makers of our time.

Hockney, Printmaker, Dulwich Picture Gallery, London SE21 (020 8693 5254) to 11 May