CARRIE MAE WEEMS

by Lori Zimmer

October 9, 2013

Carrie Mae Weems: Thirty Years of Truth

Passionate about art?

Summing up Carrie Mae Weems’s body of work under the title “Three Decades of Photography and Video” may seem like a gross underestimation, but the stark title lets the artist’s powerful work speak for itself. The exhibition of photographs, written texts, audio recordings, fabric banners and videos is making its way around museums across the country, before it makes its final stop at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York in January of 2014. Two hundred of the recent MacArthur Grant winner’s semi-autobiographical works make up the cohesive exhibition, as well as a 280 page catalog, edited by Kathryn E. Delmez.

Weems’ work has always towed the line between racial truths and social injustices, pushing the boundaries of history to understand the constraints of the present. Being a 60 year old African American woman, her work is often lumped into the category of racially driven art, but the racial issues pressed in her photographs only scratch the surface of their underlying meaning. Weems uses intimate and familial scenes to explore themes of gender, family, class, and power in America, deliberately shooting in a documentary style to evoke a certain feeling of reality, and often using sarcasm or humor to make serious issues more palatable to a potentially uncomfortable white viewer.

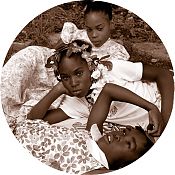

Weems began her exploration of photography in 1983 with her series Family Pictures and Stories, which meshed an autobiographical style with a narrative, using members of her own family to illustrate the historical migration of black families from South to North. The series of works that followed were as personal as the first, bringing elements of daily life and personal relationships into the reality of racial, class and gender discrimination. The 1988 series Ain’t Jokin’ uses text and racial jokes to bring prejudicial acts from other races to the forefront, but also internalized racism felt within the African American community. The Kitchen Table series from 1990 explores issues of beauty, sensuality, gender and the roles of tradition in family life, by showing domestic scenes of a family around a table – herself cast as the often strong, sometimes demure matriarch. In each photograph the matriarch is portrayed exuding different levels of confidence and power, as she interacts with men, her children, and other women. The complexity of a woman’s role is challenged, questioned and turned upside down, bringing to light critical problems relating to identity within the family and daily life.

As Weems became more comfortable exploring her own family, she began directing her focus to larger historical and political issues, including long standing racial stereotypes resulting from the atrocities of America’s involvement with the slave trade. Using layering of historical photographs with text, video, sound and written narrative, she enhances the visual power she has honed using photography to create effective installations about difficult issues from American history. The assemblages, along with Weems’ frank voice and presences in the work, present issues of persecution and prejudice with the voice of a story teller, rather than that of a critic or oppressed victim. The artist expertly weaves in her interest folklore to construct a dialogue that welcomes viewers to digest her messages of reality, rather than alienating them with harsh truths that many may ignore or would rather not see.

It is the straight forward presentation of these issues that makes Weems’ work so special and more importantly, powerful. Confidence exudes from her photographs with almost a polite quality, planting one foot in the male-dominated art world and the other in the role of a socio-racial historian. It is not surprising that Weems’ ability to finely balance art with racial and social issues has attracted the attention of the MacArthur Foundation, who awarded the artist with a fellowship this year. Also called the Genius Grant, the $625,000 award is given to individuals who show “exceptional merit and promise for continued and enhanced creative work,” and is awarded to candidates in fields such as computer science, ecology, chemistry, and neuroscience, and in general only a handful of winners in the creative arts.

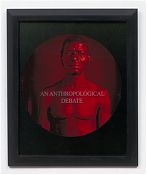

In recent years, Weems has explored the denigrated image of African Americans in cultural history, in an unmitigated series called “Slow Fade to Black,” where photographs of female icons like Josephine Baker, Dorothy Dandridge and Nina Simone are obscured into a blur of familiar pigment, only recognizable after a few seconds of letting the eyes adjust. This literal depiction of the loss of cultural identity compliments Weems’ oeuvre of the past thirty years, taking the visitor on a journey that engages with history that is personal, cultural and political.

Museums around the United States are showcasing the exhibition Carrie Mae Weems: Three Decades of Photography and Video, which is in the middle of a cross-country tour. Beginning at the Frist Center for the Visual Arts in Nashville, the exhibition traveled to the Portland Art Museum then to the Cleveland Museum of Art. The next stop is the Cantor Center for Visual Arts in Stanford, California, where it will open on October 16, before its final installation at the Guggenheim in New York in January of next year.